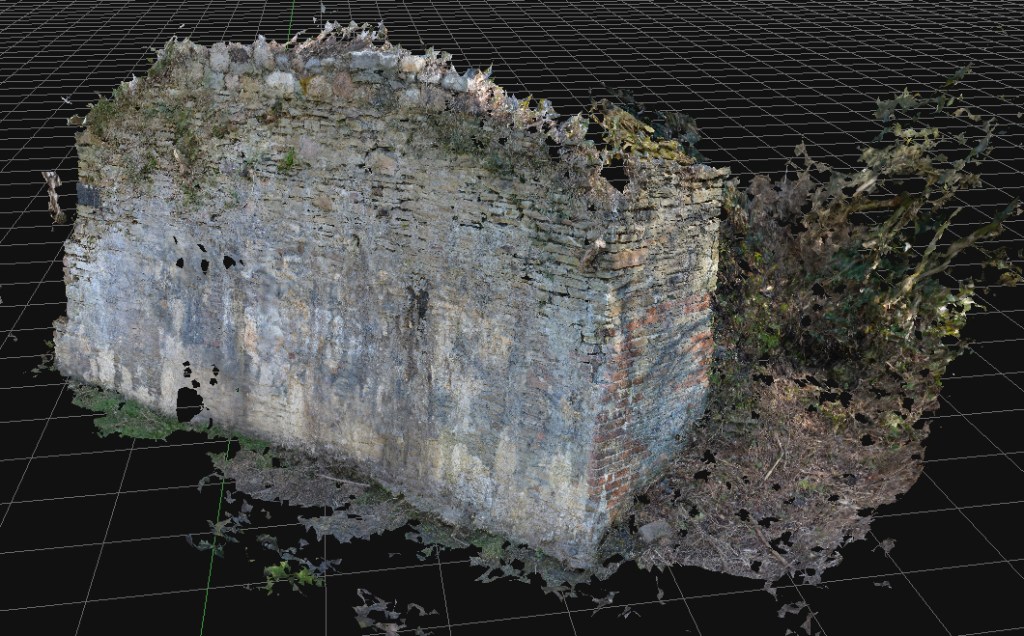

In the autumn of 2022, the local Council announced their plans to remodel the ancient Kilvey Hill landscape for a new tourism development, which would destroy the traces of thousands of years of human habitation and endeavour. The impending destruction led me to do what I could to record the history, ecology, biodiversity and Geoheritage of what is a significantly under-recorded landscape with considerable potential for education, well-being and climate change management.

Documenting the history and biodiversity was relatively straightforward, albeit a challenge to perceptions regarding a large area of land that many people see but few have experienced and even fewer understand. I remember one comment from the local authority about ‘there is nothing up there’. A comment I later understood as a self-serving phrase to make the destruction and loss more comfortable for planning permissions.

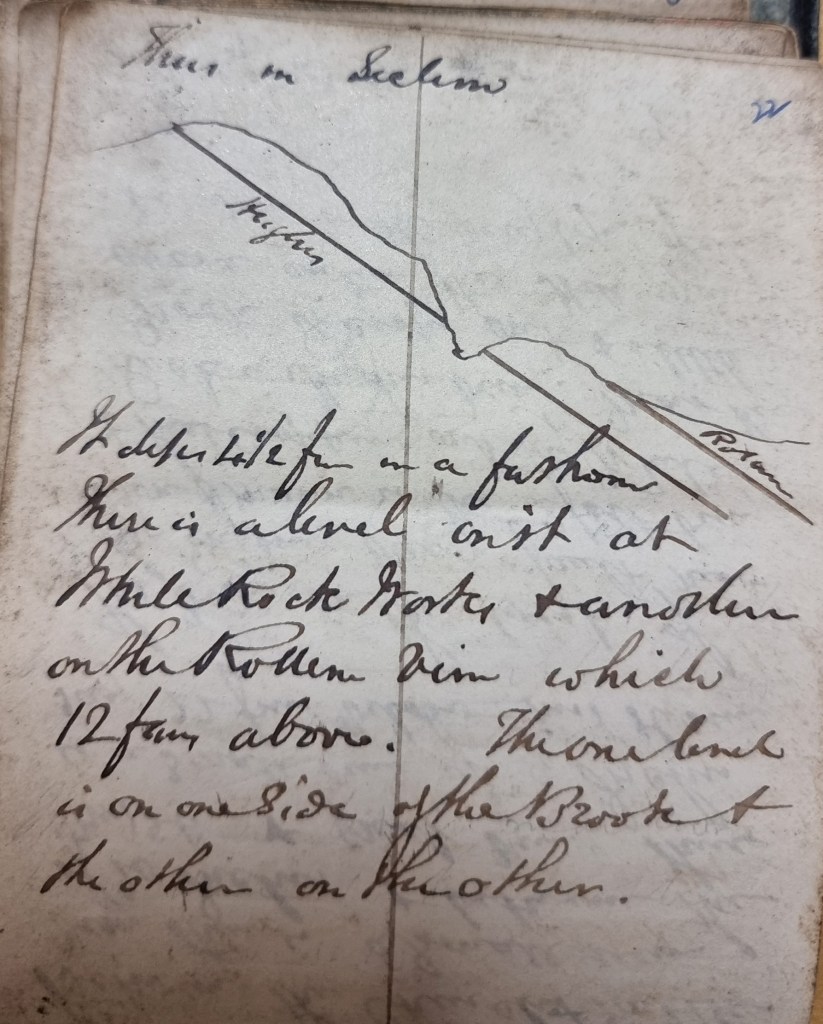

I suppose my perceptions were different, having had the advantage of a geological education at school and undergraduate level, including a hectic month of field mapping coastal regions of the Isle of Wight back in the day. I hadn’t appreciated how much of that had stuck with me until I needed to explore the Geodiversity of the Hill through documents, fieldwork and the wonderful archive of the British Geological Survey.

The fact that the natural heritage of any country includes its geological heritage is now slipping away from us. The wonderful naturalists’ clubs of the early twentieth century, such as the Swansea Scientific and Field Naturalists’ Society, were a broad church to all aspects of nature, including geology. But they have disappeared in the swing towards wildlife rather than general nature conservation, which has permanently obfuscated much of our wonderful Welsh geological heritage. The process accelerated as Naturalists’ Societies changed their names to Wildlife Trusts.

The collapse of geology as a subject deemed worthy of learning and the dissolution of the geological part of the National Museum for Wales have meant that describing the significance of geological sites has become challenging, as basic literacy in the nature of rocks and the landscape is in freefall.

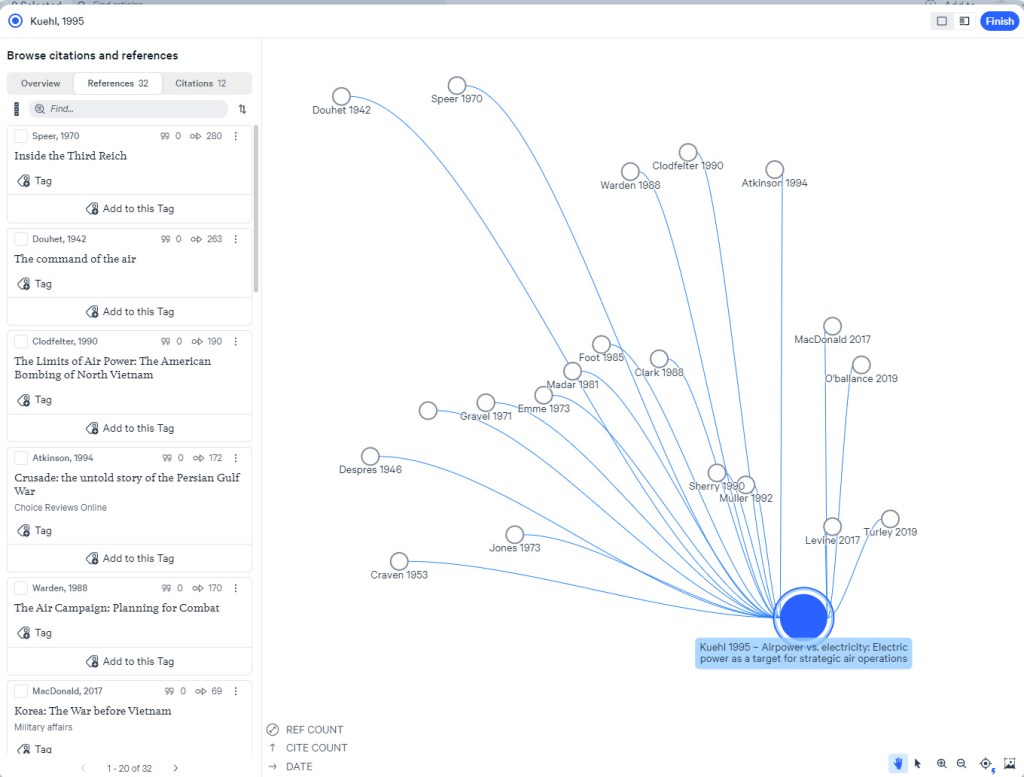

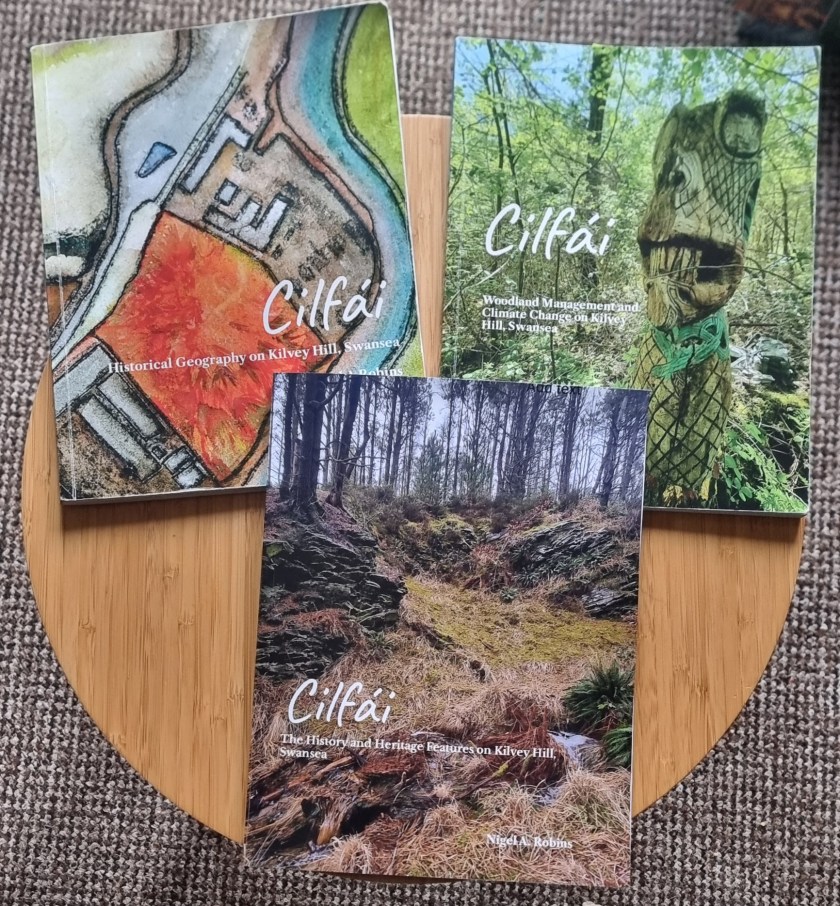

Geoheritage and Geodiversity featured strongly in my first book on the history of Cilfái, not least because it was good history as well as good geology (Robins 2023a). I sought to highlight the significance to local heritage of the geology by separating ecology, biodiversity and climate change into the second Cilfái book (Robins 2023b). However, I felt my treatment of Geoheritage in the first book was not enough. I included a more substantial piece on Swansea’s coal history in my book on the Swansea Foxhole Coal Staithes, but the rich history of William Logan, Hendry de La Beche and Aubrey Strahan clearly deserves more (Robins 2025).

‘Every outcrop has the potential to be great’ (Clary, Pyle, and Andrews 2024) was an opening line to a recent special publication from the Geological Society. It’s a great opening line, and it sets a very positive note for a lively discussion on Geoheritage on a landscape scale. It’s a sentiment that is less positively upheld in Wales where our process of listing or recording sites of geological interest is haphazard and starved of interest and funds.

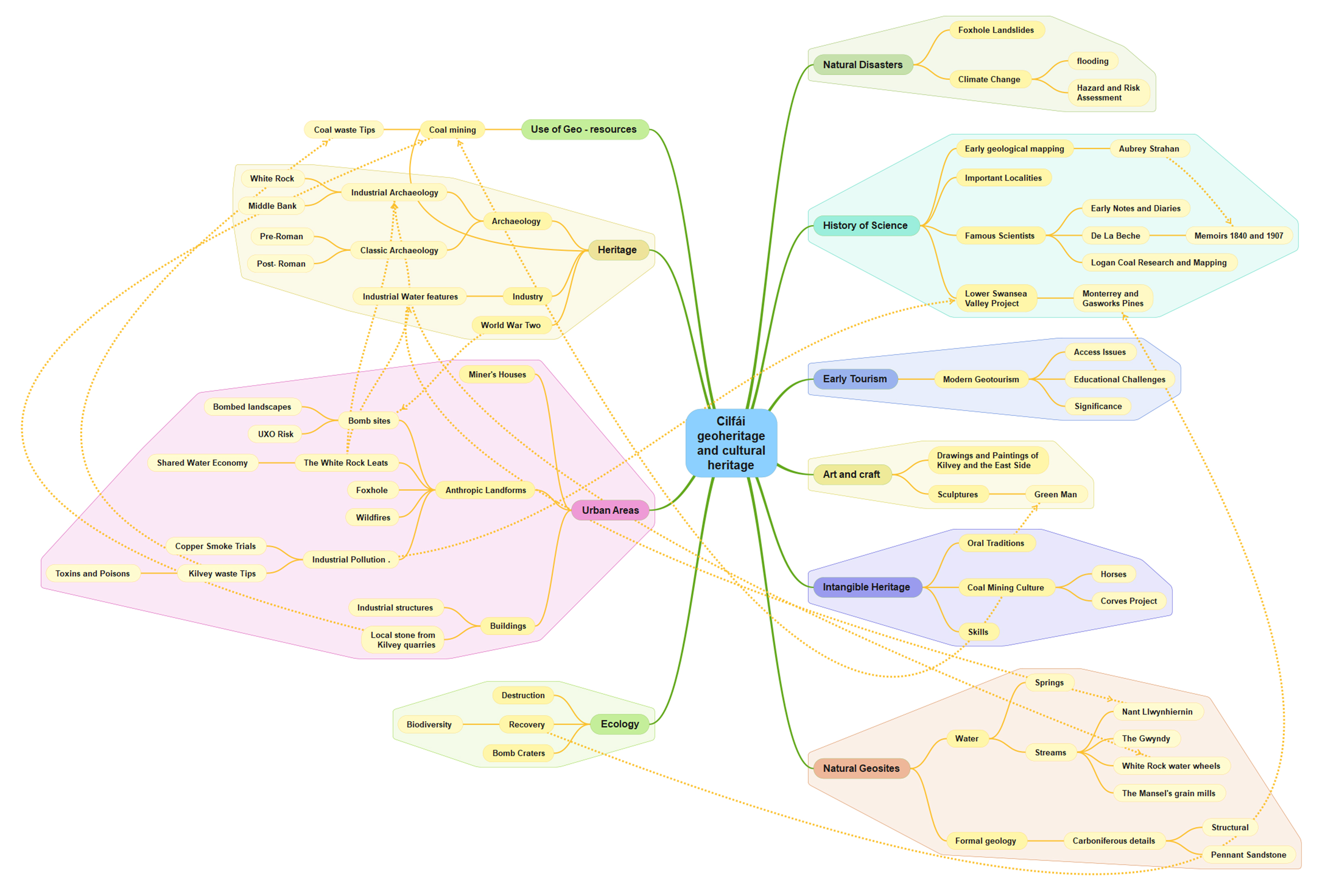

Nevertheless, the listing of a Kilvey site visit on the coming UNESCO International Geodiversity Day is a good opportunity to explore and reassess local Geoheritage. In preparing information for the International Geodiversity Day, I was particularly struck by a recent article linking Geoheritage and Cultural Heritage (Pijet-Migón and Migón 2022). The authors have introduced a model of themes at the Geoheritage-Cultural Heritage ‘interface’. It’s a very useful summary of what to explore or be aware of when revisiting geological sites. It helps move forward from traditional geological guides and texts (Owen 1973), which, although very useful, need to be modernised and broader in scope and engagement for a new generation.

Although the Pijet-Migón model doesn’t fit everything, for example, it can be broadened to explore the link between Biodiversity and Geodiversity, it is very useful. Here’s the Cilfái Geoheritage Landscape filtered through an amended model:

Clary, Renee M., Eric J. Pyle, and William Andrews. 2024. ‘Encompassing Geoheritage’s Multiple Voices, Multiple Venues and Multi-Disciplinarity’, Geology’s Significant Sites and Their Contributions to Geoheritage, no. Special Publication 543, pp. 1–7, doi:10.1144/SP543-2024-34

Owen, T.R. 1973. Geology Explained in South Wales (David & Charles)

Pijet-Migón, Edyta, and Piotr Migón. 2022. ‘Geoheritage and Cultural Heritage – A Review of Recurrent and Interlinked Themes’, Geosciences, 12.98, doi:10.3390/geosciences12020098

Robins, Nigel A. 2023a. Cilfái: Historical Geography on Kilvey Hill, Swansea (Nyddfwch)

——. 2023b. Cilfái: Woodland Management and Climate Change on Kilvey Hill, Swansea (Nyddfwch)

——. 2025. Foxhole River Staithes and Swansea Coal (Nyddfwch)