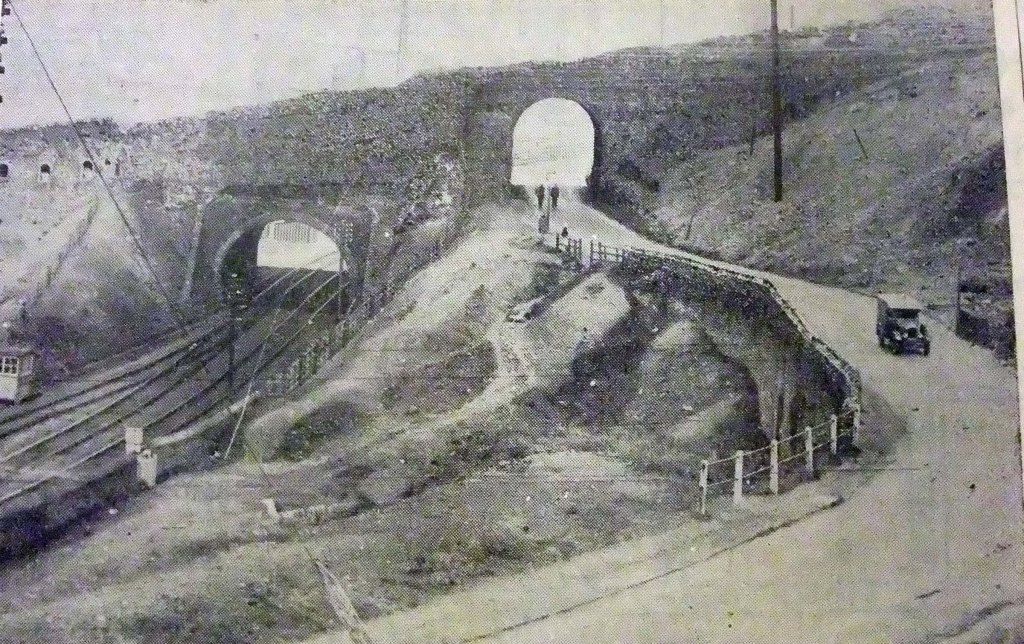

When I wrote the first Cilfái book, on the history of the hill, my views were strongly coloured by the work of American ecofeminist Carolyn Merchant. Merchant has many talents, but one of her earliest books was titled ‘The Death of Nature’ (The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology and the Scientific Revolution )A strong title, and I can recall being quite challenged by it when I first read it in the early 1980s. Merchant is a formidable historian of science and her book explored the importance of gender in early writing on nature. Her grasp on European industrial history was superb and her interpretation of how the understanding of nature changed in the Industrial Revolution from an organic or female conception through to the mechanistic model of coalfields and resources.

Alongside this, the destruction of people’s rights and freedoms throughout the medieval period by greedy landlords had a profound impact on the perception of land and property. The medieval economy of Cilfái was based on organic and renewable energy sources (wood, water, and wind), the emerging capitalist economy of the Mansel family was based on coal and metals which transformed the nature of the hill. The changes on Cilfái over the past few centuries are confirmation of Merchant’s theories.

In one of her most famous statements…

The female earth was central to organic cosmology that was undermined by the Scientific Revolution and the rise of a market-oriented culture … for sixteenth-century Europeans the root metaphor binding together the self, society and the cosmos was that of an organism … organismic theory emphasized interdependence among the parts of the human body, subordination of individual to communal purposes in family, community, and state, and vital life permeate the cosmos to the lowliest stone