The latest press release from Welsh Government about the National Forest for Wales confirmed that Swansea’s Penllergare Valley Woods has been confirmed as a National Forest site. I think this makes it one of the hundred announced sites so far.

It is a clever bit of policy from Welsh Labour and throws a bit of recognition and identity branding the way of some struggling woodland sites. Creating a Welsh ‘network’, however fragmented, can only be a good idea.

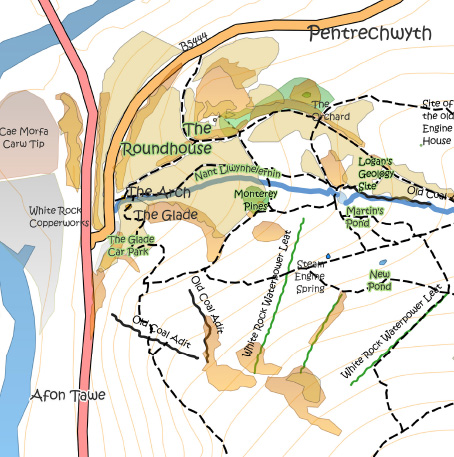

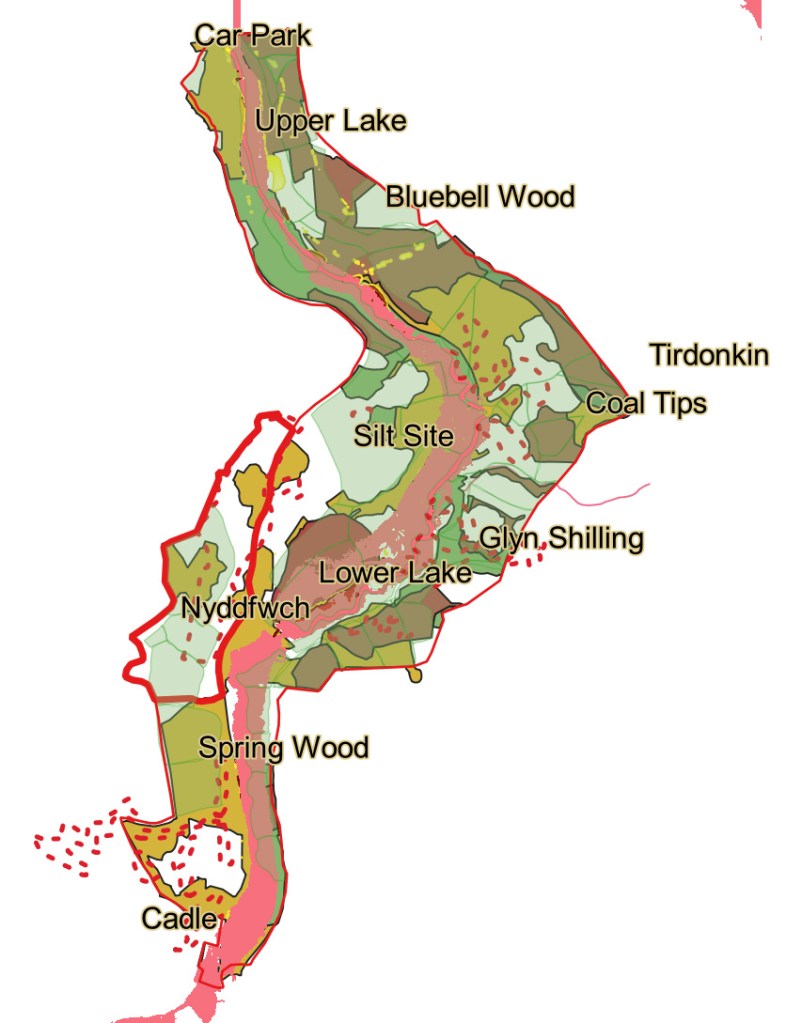

The name of Penllergare is as confusing as its location. It is probably an anglicisation of nearby Penllergaer. The lottery-funded restoration project adopted the name from the long-gone mansion owned by the Llewelyn family. The awkward anglicisation always makes me uncomfortable and I tend to refer to the area as the Llan Valley or Nyddfwch which were earlier locality names and are far more in keeping with modern sensibilities.

The valley woodlands thoroughly deserve inclusion in the National Forest list. I spent nearly ten wonderful years surveying and researching the landscape and woodlands until I felt compelled to leave in the face of the ugly politics and personalities that run the charity. Some of the staff and volunteers I worked with were some of the finest people I ever experienced in conservation circles, although all have been hounded out by the organisation, which is such a shame.

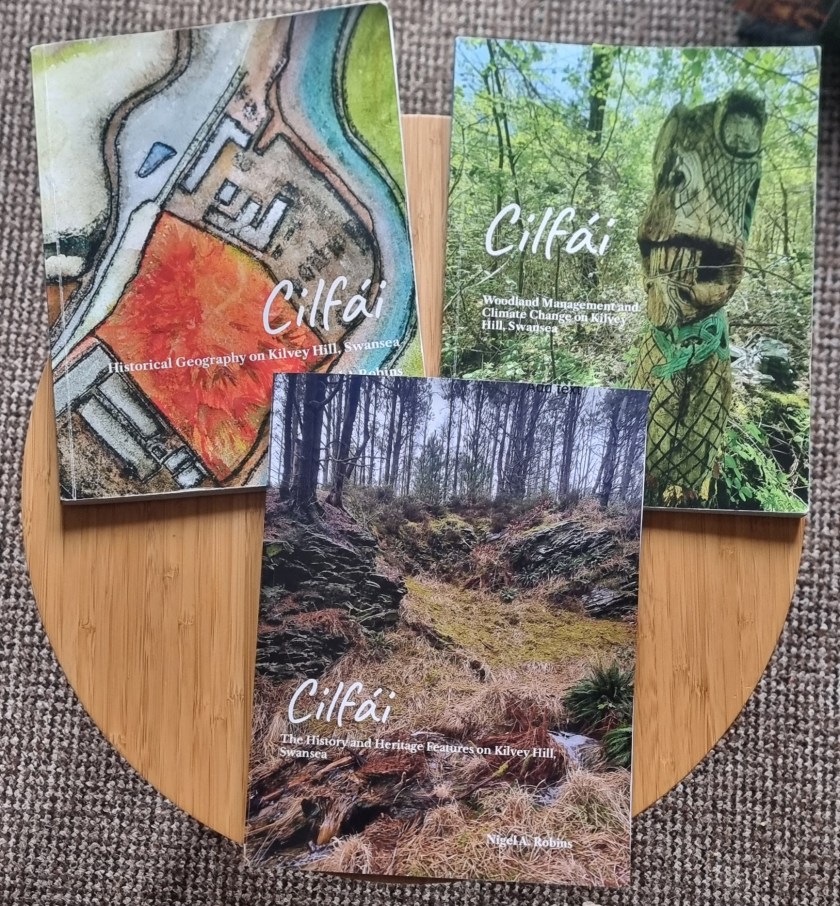

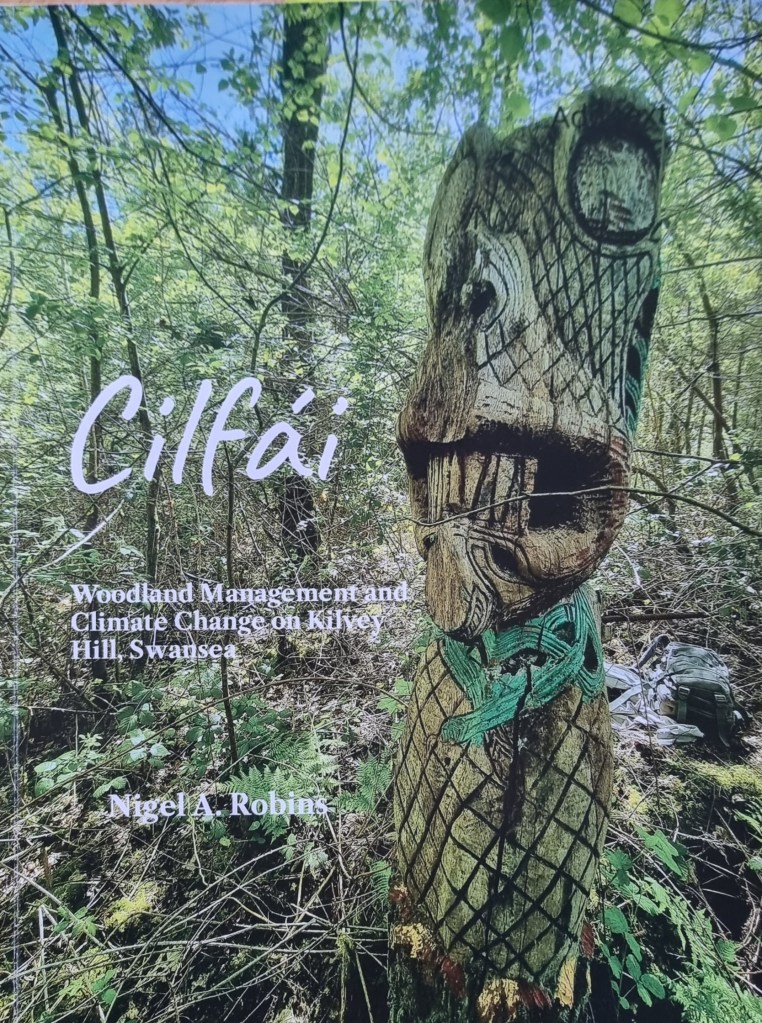

The original mission of the lottery-funded project was to recreate the nineteenth-century estate gardens of the Llewelyn family. It was centred on making something of the remaining walled garden and the paths and planting of the Llewelyns, a wonderful collection of exotic trees, native (1800s) planting, and a collection of Rhododendrons. The premise was ambitious in the early 2000s, and many of us were surprised that it got funding, as we knew the concept was challenging because of climate change and the lack of surviving substantive features. I think the charity running the place is now pressing for more money to keep the place going. Some of you who came to my Environment Centre lectures may remember I compared the limited effectiveness of money invested in Penllergare with the far better return on investment of money spent on Cilfái.

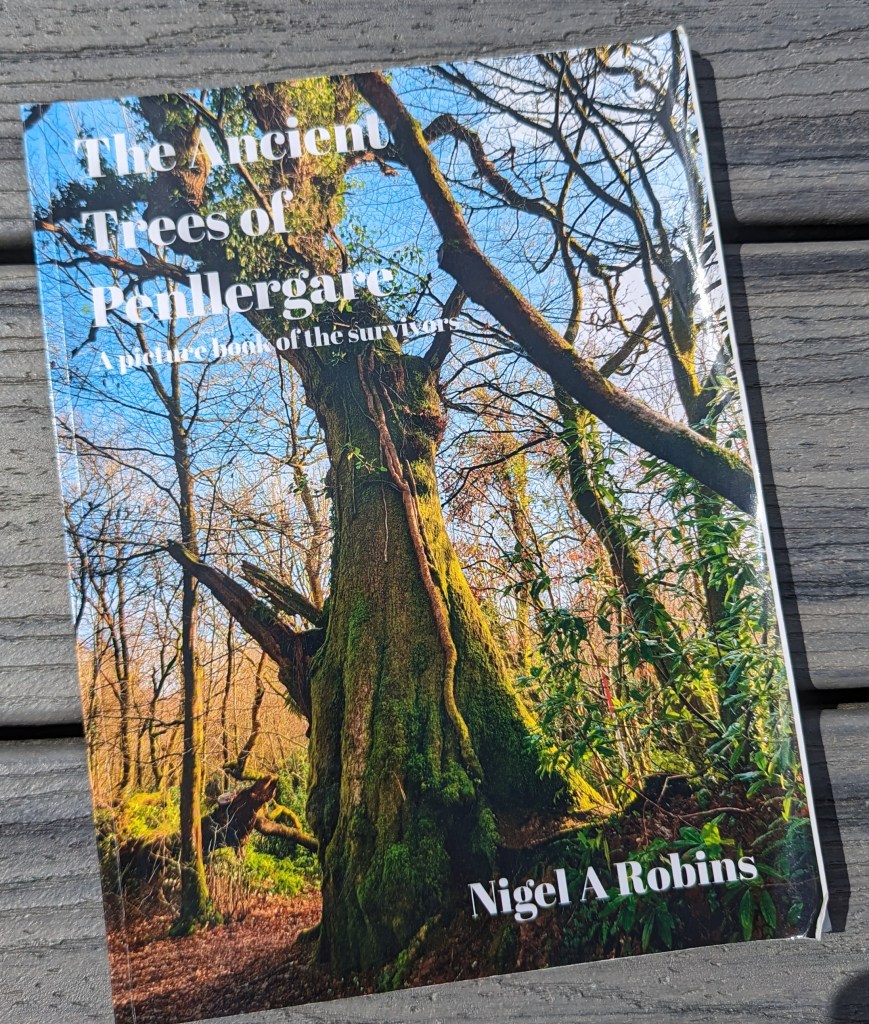

The wider area of woodland contains significant ancient trees, 1950s Forestry Commission planting and a spectacular collection of unusual and exotic tree species (the remnants of the nineteenth-century garden). Much is made of the links to the Llewelyn family, although they abandoned the site for a nicer house elsewhere. I imagine the family’s estate managers will be unhappy at this latest National Forest status as they were hell-bent on selling for housing; the land is on a short lease for the charity.

The history of the nineteenth century is only of limited significance. Far more interesting is the history of the valley in the early 1700s, when it was devastated by coal mining. So, the land is a good example of early Welsh industrialisation and the recovery after that, when the coal was worked out in the 1790s. The ancient trees are an incredible survival from the coal mining devastation of the 1700s and were probably rejected for harvesting as timber because of their shape. I prepared a draft book on the woodlands a few years ago, and now may be the time to turn it into a real entity.

I used to take many groups into the woods to explore the woodland, let me know if you’re interested and I’ll put together a walk.