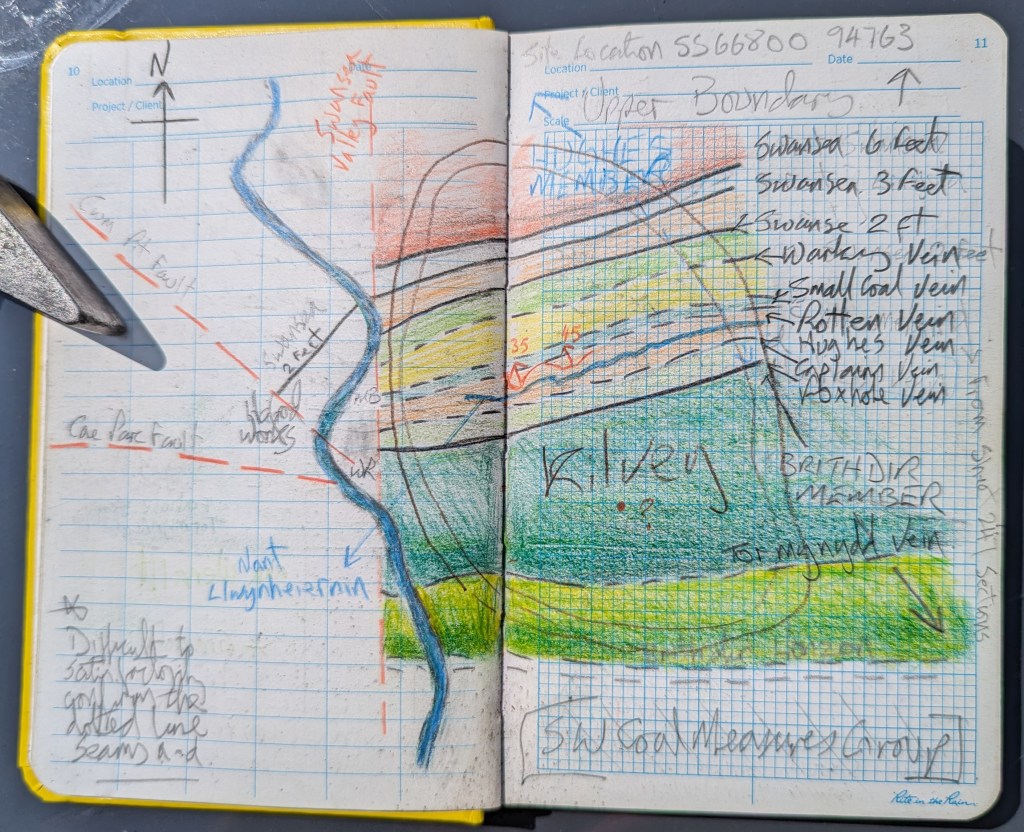

Starting the new book project. I initially looked at the war diaries of Bristol Channel U-boats back in the 1990s. Research is now easier as more primary records have been released by US archives, at least until the latest President Trump directives close everything down. Modern technology in GIS and GPS has made map research much easier, and I am busy tracking down the original locations of magnetic mines originally planted in Swansea Bay and around the Scarweather Lightship. There have already been a few surprises as the mapping throws up all sorts of questions and new insights into the highly technical war of minelaying and minesweeping in the Bristol Channel.

The war against the U-boats is a complex subject to research thoroughly. There was considerable secrecy on both sides, and very often, the knowledge gap has been filled with wild speculation and inaccurate writing. This means I’ve had to reject a lot of secondary sources that continue to repeat what I’ve learned to call the ‘BBC History’ approach of ruthlessly clever Germans versus plucky eccentric Englishmen. There is also a surprising amount of rivalry and bias between British and US naval sources, both in the 1940s and in the present day. Again, I’ve learned to be scrupulous in testing opinions by viewing primary sources rather than derived history, often from writers who have not worked in the original German language sources.

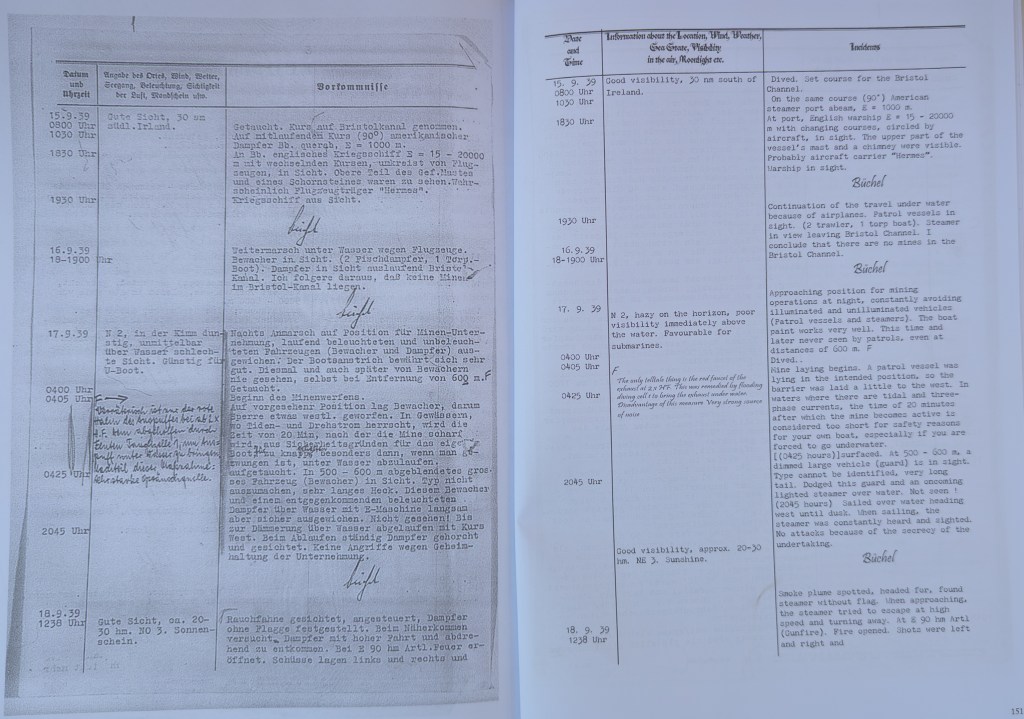

Some initial work was included as an Annexe in ‘Eye of the Eagle’ where I looked at the war diary of U32 as it laid magnetic mines near the Scarweather Lightship in 1939. The new work looks at all the other U-boats that came into Swansea Bay in the early years of the war. Again, it reinforces the crucial role Swansea had in the minds of the German naval staff.