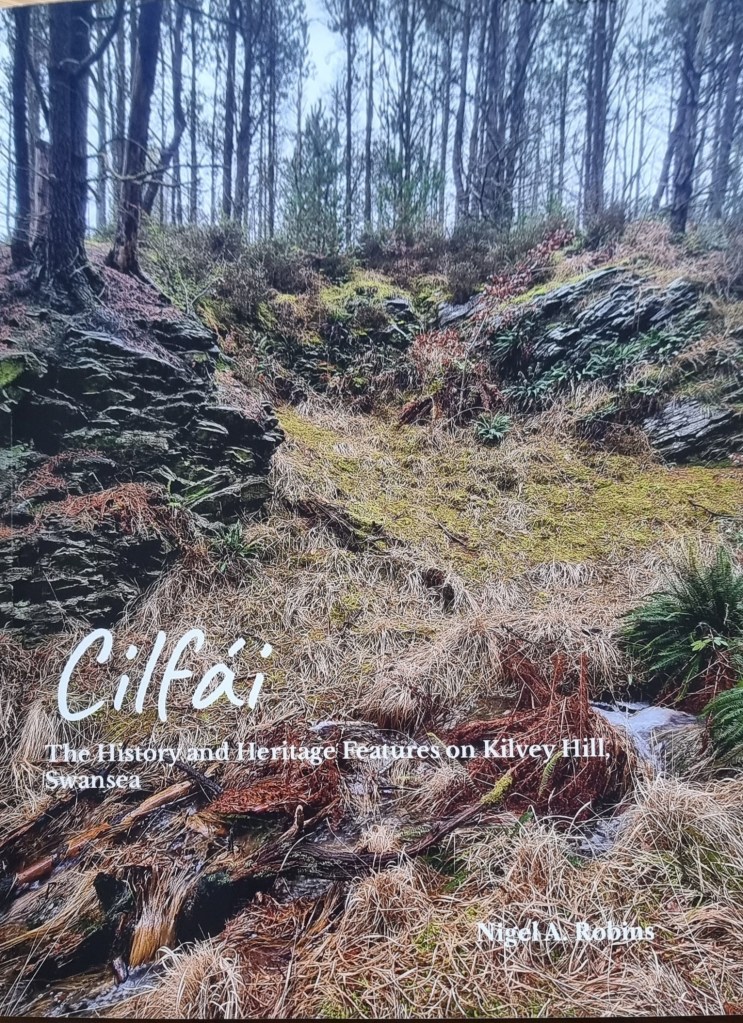

In researching the geology of Kilvey Hill, several issues quickly come to light.

The first is how little geology is actually being taught or even followed as a hobby any more. This is quite remarkable given the massive part Swansea’s geology has played in the history of the town. Swansea’s underlying coal resources were a massive factor in the development and growth of the eighteenth-century town. Without coal, there would have been no copper smelting, and Swansea would probably have remained the ‘Brighton of Wales’ (Boorman 1986). All the more remarkable when you consider that geology was an immensely popular subject for study in Swansea from the 1830s, and a century later, a large part of the University College of Swansea (Owen 1973; 1974). The geology of Kilvey became a training ground for William Logan when he taught himself about Swansea coal and rocks in the 1830s. Some of this will be a central theme in my guided walks for UNESCO Geodiversity Day in October.

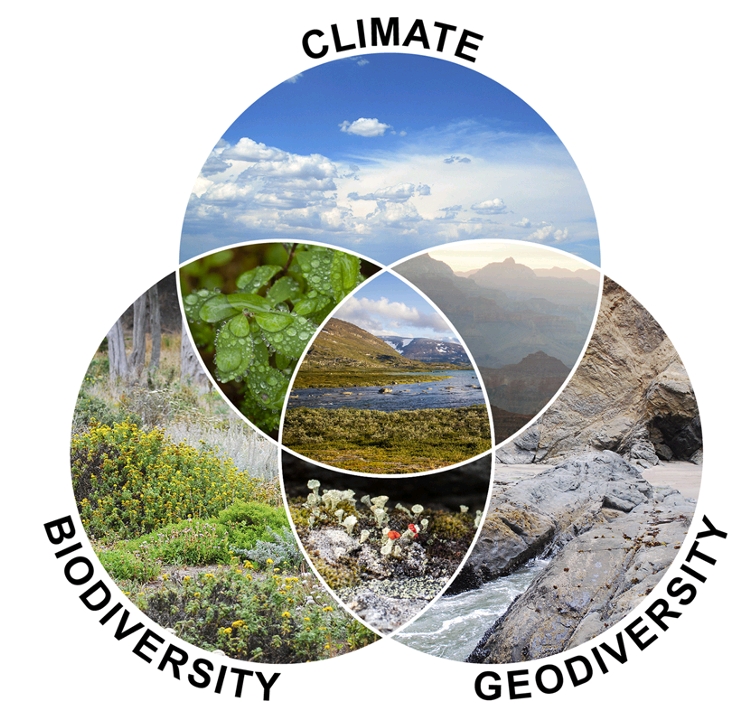

Although people are now fully aware of the importance of biodiversity to our lives, less is appreciated about the non-living side of the equation — the Geodiversity of the underlying rocks and soils. Geodiversity is the foundation of the ecological life on the hill. The underlying soils, waste tips, streams, and geological features all influence the recovery of life after the cataclysmic pollution that killed everything on the hill in the nineteenth century.

Biodiversity, Geodiversity and Climate are all interlinked to give us the environment we live within, or are responsible for (Tukiainen, Toivanen, and Maliniemi 2023). Kilvey’s ecosystem was destroyed by industry, coal mines destroyed the water table, and the recovery process has been long and uncertain, but in some places spectacular. It remains a tragedy that some of the recovered green areas of the hill will shortly be destroyed again by the local Council.

Boorman, David. 1986. The Brighton of Wales: Swansea as a Fashionable Seaside Resort, c.1780-1830 (Swansea Little Theatre Company)

Owen, T.R. 1973. Geology Explained in South Wales (David & Charles)

—— (ed.). 1974. The Upper Palaeozoic and Post-Palaeozoic Rocks of Wales (University of Wales Press)

Tukiainen, Helena, Maija Toivanen, and Tuija Maliniemi. 2023. ‘Geodiversity and Biodiversity’, in Visages of Geodiversity and Geoheritage, Special Publications, 530 (Geological Society of London), pp. 31–47