Yesterday (18 April 2024), Swansea Council took a first public step towards leasing or selling a large part of Kilvey Hill to a foreign tourist company. The decision was a milestone in a process started in secret in 2017. The years since have seen covert land assembly, including a particularly unpleasant land steal by Swansea Council, as politicians and staff work officially or otherwise to facilitate the plans of the foreign tourist company.

Our abysmal local government system’s callous, unthinking bureaucratic jargon describes the potential sell-off as a ‘disposal,’ as if the land were used tissue. This had happened before when previous generations and local councils enthusiastically embraced industrial development and regarded the destruction of nineteenth-century Kilvey as merely ‘collateral damage’ … a disposal problem.

The transformation of Swansea from an attractive resort to an industrial black spot was beautifully catalogued in a 1986 book called ‘The Brighton of Wales’ (Boorman 1986). Boorman traces the point of departure from unspoiled beaches to the Lower Swansea Valley industrial magnet. Now, the wheel has turned full circle as a desperate local authority, in acts of unbridled boosterism, refers to Swansea as a world-class tourism destination. I can only assume Councillors haven’t recently made that dangerous walk from Swansea railway station down the High Street.

There will be plenty of economic arguments for the developments to go ahead based largely on optimism and faith in the future. One thing is certain: the enthusiasts for the scheme and all the positive comments on those strange news sites don’t live there.

The Council and the local communities have a lot to be proud of regarding environmental recovery and the new uses of the urban woodlands on the east side. I wish the politicians would recognise this instead of chasing a handful of ice cream-selling jobs.

Boorman, David. 1986. The Brighton of Wales: Swansea as a Fashionable Seaside Resort, c.1780-1830 (Swansea: Swansea Little Theatre Company)

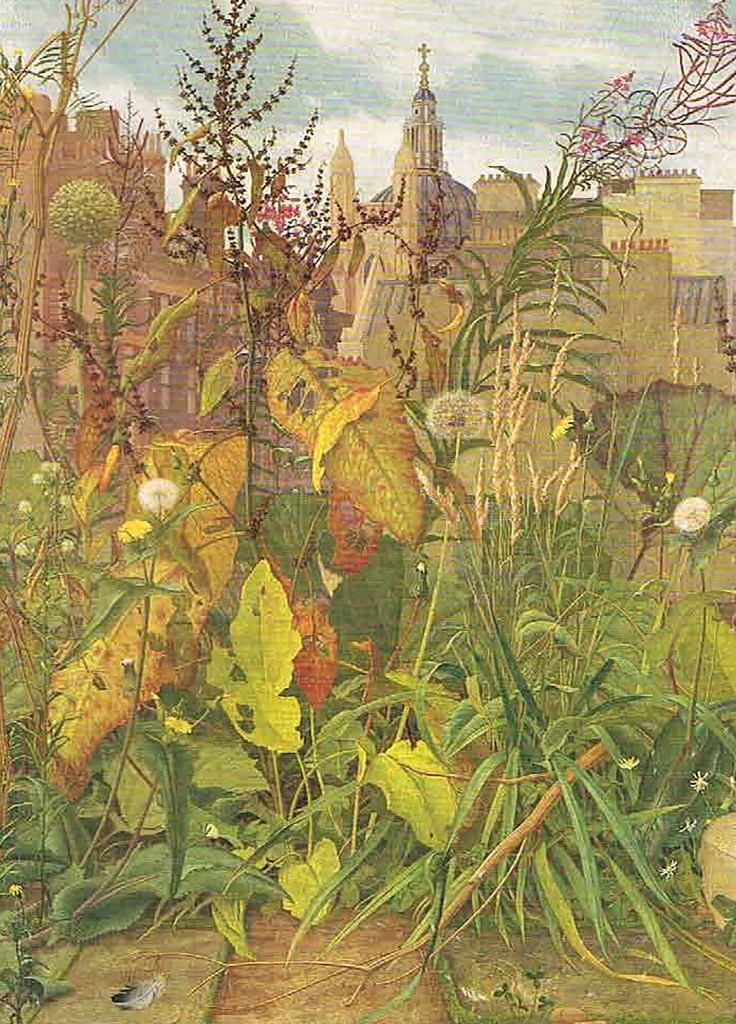

Below: The planned Skyline buildings. Incredibly, this picture is of part of Kilvey Hill that Swansea Council don’t actually own.