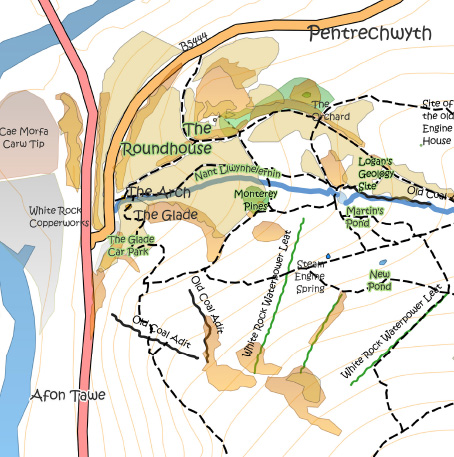

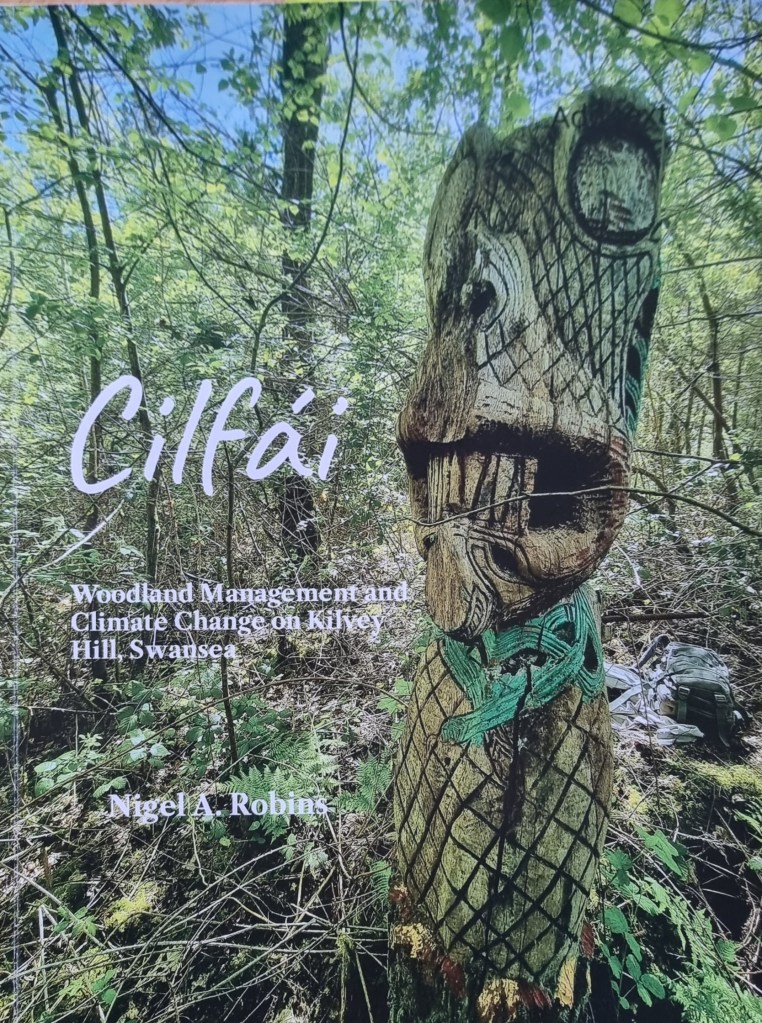

Cilfái’s connectivity to other wildlife and natural habitats is not just a concern, it’s a massive issue. The dangerous main roads dominate the wider extent, west towards the river and north towards what was the Enterprise Zone. Within the woodlands, further development for bike paths, walking trails and cable car routes are all immediate risks for ruinous fragmentation. The width of paths and firebreaks and cableways and how we manage the woodland edge habitats are crucial. Cilfái’s wider nature network must be urgently mapped and managed using the ten well-known best practice principles (Crick and others 2020a: 91–101).

1. Understand the Place. Understanding the community and the natural networks that are in place.

2. Create a Vision. Create a future that is understandable and engages the biggest stakeholders, usually the local communities, animals and plants, and those responsible for caring for and maintaining the land.

3. Involve People. Communication, engagement and consultation are tremendously important. Do we see that commitment from local politicians?

4. Create Core Sites. The central Cilfái woodland is our core site.

5. Build Resilience. This is protection against climate change-related events such as drought, torrential rain, wildfires, and temperature extremes. I describe some of these in the book.

6. Embrace Dynamism. Nature changes constantly. Change can happen in a matter of minutes: a tree blows down, a stream bursts its banks, or a rockfall changes the shape of the land. We can’t keep spending money on keeping things ‘as they are’. Is expensively recreating a nineteenth-century landscape that relies on money, gardening, water and stable weather and climate (as they do at Penllergare Country Park) even possible in the modern world? We must accept and adapt to our situation, not the situation we would like to be in.

7. Encourage Diversity. There is genetic variability, species diversity, ecosystem diversity and phylogenetic diversity. Diversity is not distributed evenly on Cilfái. The ecosystem we see building on the hill results from 50 years of growth and change.It should be allowed to develop naturally. The notion that a local Council or a private tourism company can care for the land is an outrageous conceit.

8. Think ‘Networks!’ Plants, animals, and people move and live in connected networks.

9. Start Now, but Plan Long-term. Short-term is about 3 years, long-term is about 50 or more. Nobody knows what the world will be like in 50 years.

10. Monitor Progress. We can’t understand change if we don’t observe it constantly. A 3-day ecological survey by a non-local contract ecology firm on behalf of a foreign tourist company doesn’t cut it.

However, there will always be uncertainty about what Cilfái can contain because it is always prone to extreme disturbance.

Crick, H.Q.P., I.E. Crosher, C.P. Mainstone, S.D. Taylor, A Wharton, and others. 2020. Nature Networks: A Summary for Practitioners (York: Natural England)