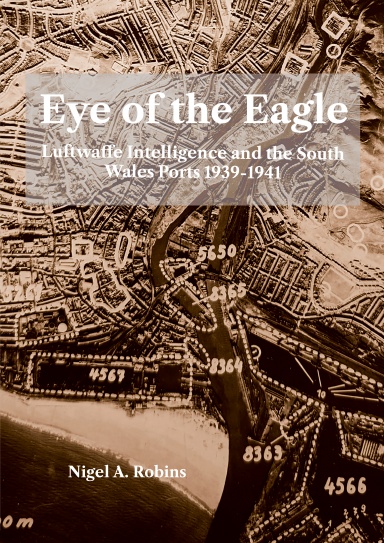

Just starting a new research project on the 1940s incendiary bomb attacks on Swansea. Although a few books have been written on wartime Swansea, the reliability can be suspect because of the lack of documentary records. The primary source is still John Alban’s keystone work on some of the archival sources that survived (Alban 1994). The response of a local authority to the challenges of an intense air attack varied widely across the country and has been the subject of a growing body of research, such as this thesis from 2020 (Wareham 2020)In this study, the author examines Cardiff Council’s response to wartime life and air attacks. It’s a mixed bag of successes and failures as the Council struggled to meet the challenges of maintaining services under air attacks. Some local authorities did little to meet their responsibilities, and civilians have died in various towns where bomb shelters, services and food supplies were poorly managed. As historians, we are not helped by the limited nature of the official history of civil defence, which barely investigated matters outside London (O’Brien 1955).

Swansea’s air raid precautions and defences worked well, and senior members of the Churchill government and officials of various agencies praised the efficiency of their response. However, local Swansea politicians criticised them and insisted on complaining that the ARP staff did not sufficiently recognise their role as politicians even amid incredible tragedy of 1941 (Alban 1994: 59–61).

Understanding the situation faced in the Blitz of February 1941 relies heavily on understanding the role of the ARP Controller, who led the entire local authority response to the bombing. For Swansea, this was the Town Clerk Howell Lang Lang-Coath. He was a veteran of over thirty years of Swansea’s local government processes, but at the end of his career, at sixty-six years old, his leadership and authority did much to save lives during and after the raids.

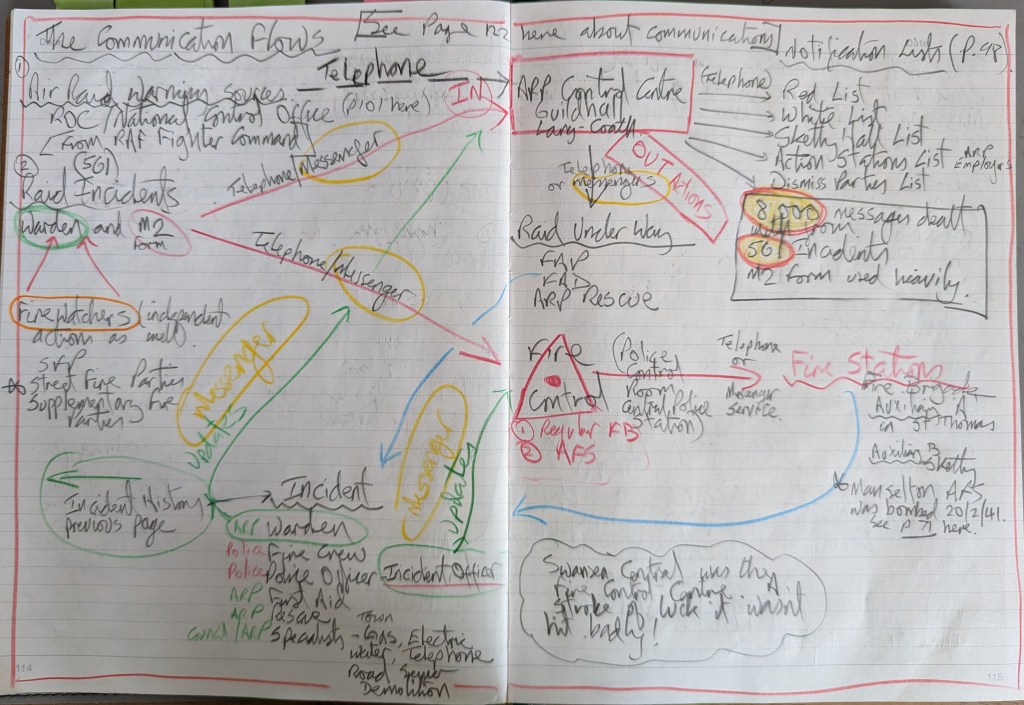

Understanding his role and effectiveness relies on understanding his communication flows and processes as he managed the ARP response from his control room in the Guildhall in Swansea. The dearth of contemporary records has meant I have had to reconstruct the communication flows from a wide range of local sources. Here’s my first pass through the information. Imagine having a small team of secretaries having to deal with over 8,000 messages for 561 incidents and controlling First Aid, Alarms, ARP staff, Rescue, Ambulances, Gas, Electricity and Water supply in an era where communications were unreliable telephones and a network of messengers in cars and on bicycles (often teenagers).

The police forces of the country were unwilling to share or modify their status and their responsibilities even during the hardest times of the war and a dual response method was imposed on the country where ARP and Fire services were managed separately. The success of this approach depended on the personal qualities of the ARP Wardens. You can see this on the diagram with different communication flows to ARP Control (at The Guildhall) and the Fire Control Centre (at Central Police Station).

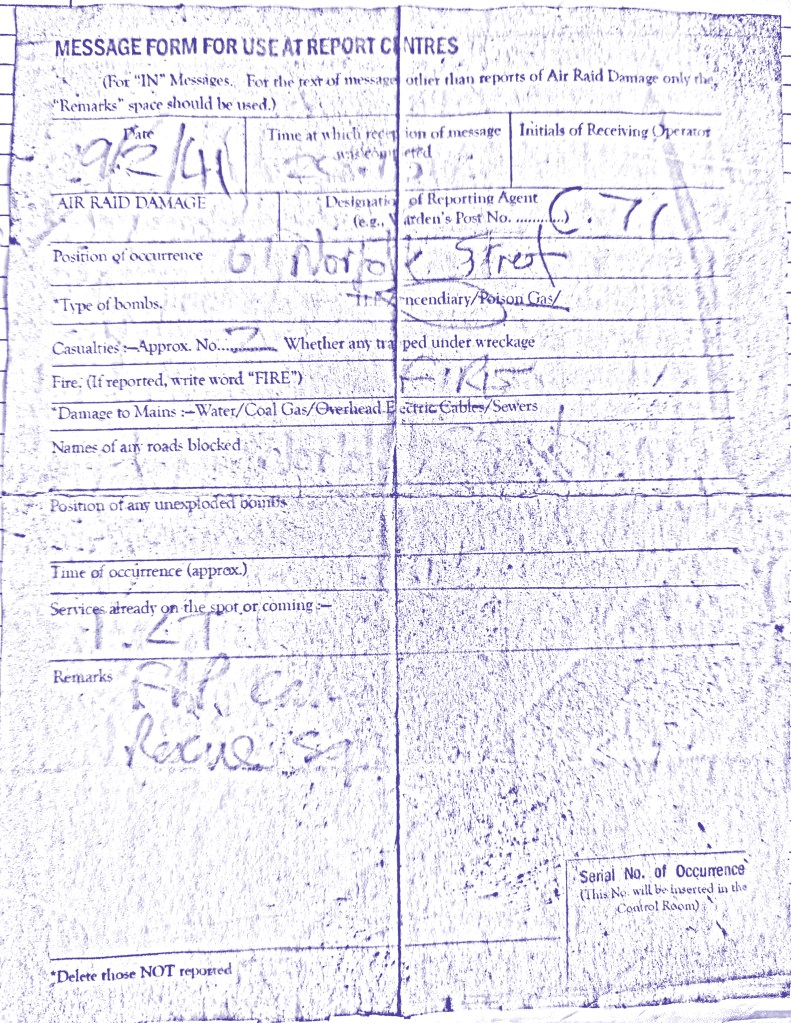

One of the surprises was the efficiency of the ARP M2 Reporting Form which allowed structured information at the correct level of detail to be quickly transmitted or passed to the staff andv the ARP Control Centre.

Alban, J.R. 1994. The Three Nights’ Blitz: Select Contemporary Reports Relating to Swansea’s Air Raids of February 1941, Studies in Swansea’s History, 3 (Swansea: City of Swansea)

O’Brien, Terence H. 1955. Civil Defence (London: HMSO)

Wareham, Evonne Elaine. 2020. ‘Serving the City: Cardiff County Borough in the Second World War’ (unpublished PhD, Cardiff: Cardiff University)