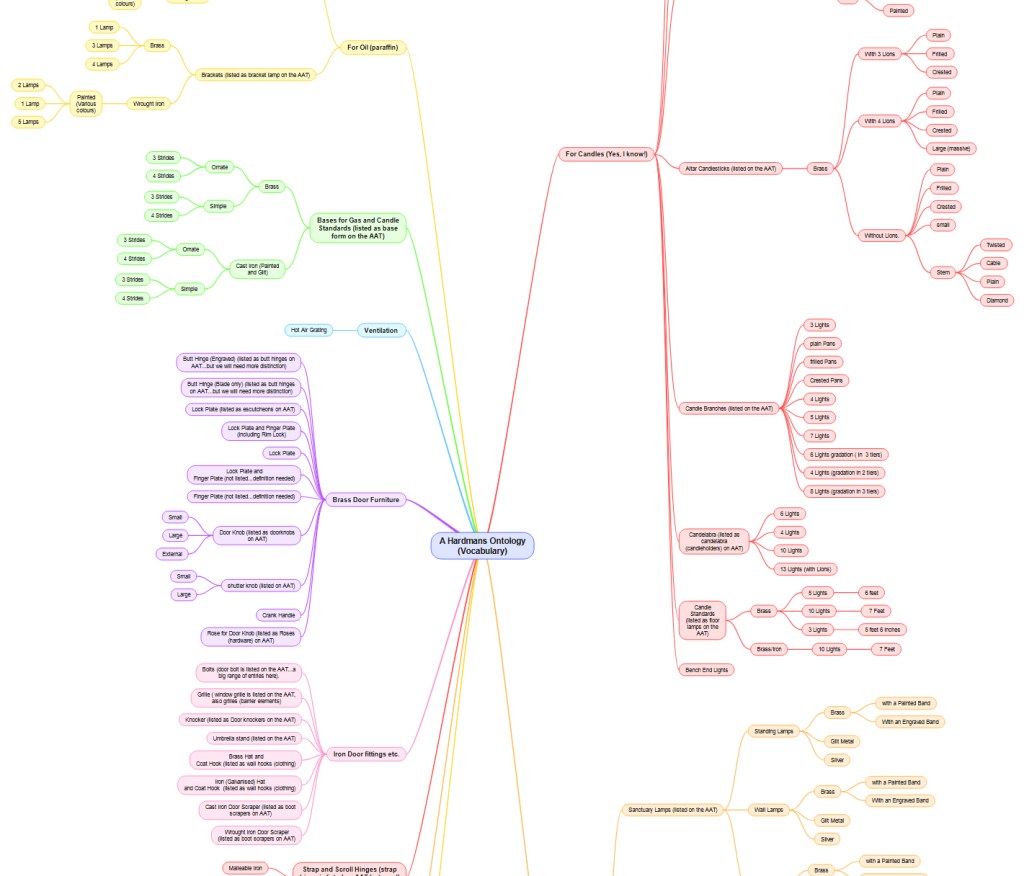

I needed to produce an ontology-based version of the ornamental metalwork output of John Hardman (https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/John_Hardman_and_Co). This originated from work in the various furniture collections of the Palace of Westminster. The Palace has large quantities of ornamental metalwork, particularly candle holders of various kinds, which were popular in the nineteenth century. Particular types of metalwork are frequently at greater risk. Whilst most can agree on the conservation case for a Hardman candle branch from the 1860s, fewer understand the extreme risk posed to classic door furniture from modern facilities management or unsympathetic cleaning regimes using abrasive chemicals. The catalogues used in the Palace were old, incomplete or had not been regularly updated or maintained through a series of digital systems. The risk to objects is large, as a comprehensive catalogue entry is often the first line of defence against damage or loss. This ontology was an attempt to communicate the scope of essential information that needed to be linked and understood for future systems.

In the 1830s, a collaboration with Augustus Pugin considerably enhanced Hardman’s output, and the Palace of Westminster has many examples of the finest Hardman output at all scales and sizes. Although I do find Hardman metalwork and fire furniture in many other large buildings.

Some large public buildings will have complex collections of ornamental metalwork, and most of this is not recognised nor its significance recorded. Items at greatest risk include door furniture, which is often exposed to damage and loss by restorers and maintenance staff who remain unaware of the significance. A good example is the use of caustic cleaning chemicals on brass door furniture, resulting in the erosion and destruction of the original finish. Another common issue is the use of the wrong size screwdrivers, resulting in broken screws that were handmade in the nineteenth century and are now irreplaceable. There is also a need to recognise the wide scope of lighting products for candles and gas available to architects and designers in Victorian Britain, many of which were installed in significant public buildings.

Whilst many items are recognised within the Getty Art and Architecture Thesaurus AAT (https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/aat/), there are several omissions, and I found that the AAT is not representative of the wide range of British artistic output in the second half of the nineteenth century.

This approach involves relating actual examples of Hardman items in British buildings to the various catalogues released by the company. Items were identified from various catalogues, museum listings, informal cleaning records, and property registers, and most were confirmed by fieldwork to confirm the physical presence (or, in some cases, survival) of the item.

Alongside the fieldwork in several house collections and the Palace of Westminster, I found the Hardman Collection at Birmingham Library of particular use, particularly the Metal Sales Ledgers and their delivery books.

Nigel A Robins. (2022). John Hardman (1880s) and Co. data and product ontology (Version 1). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6912960