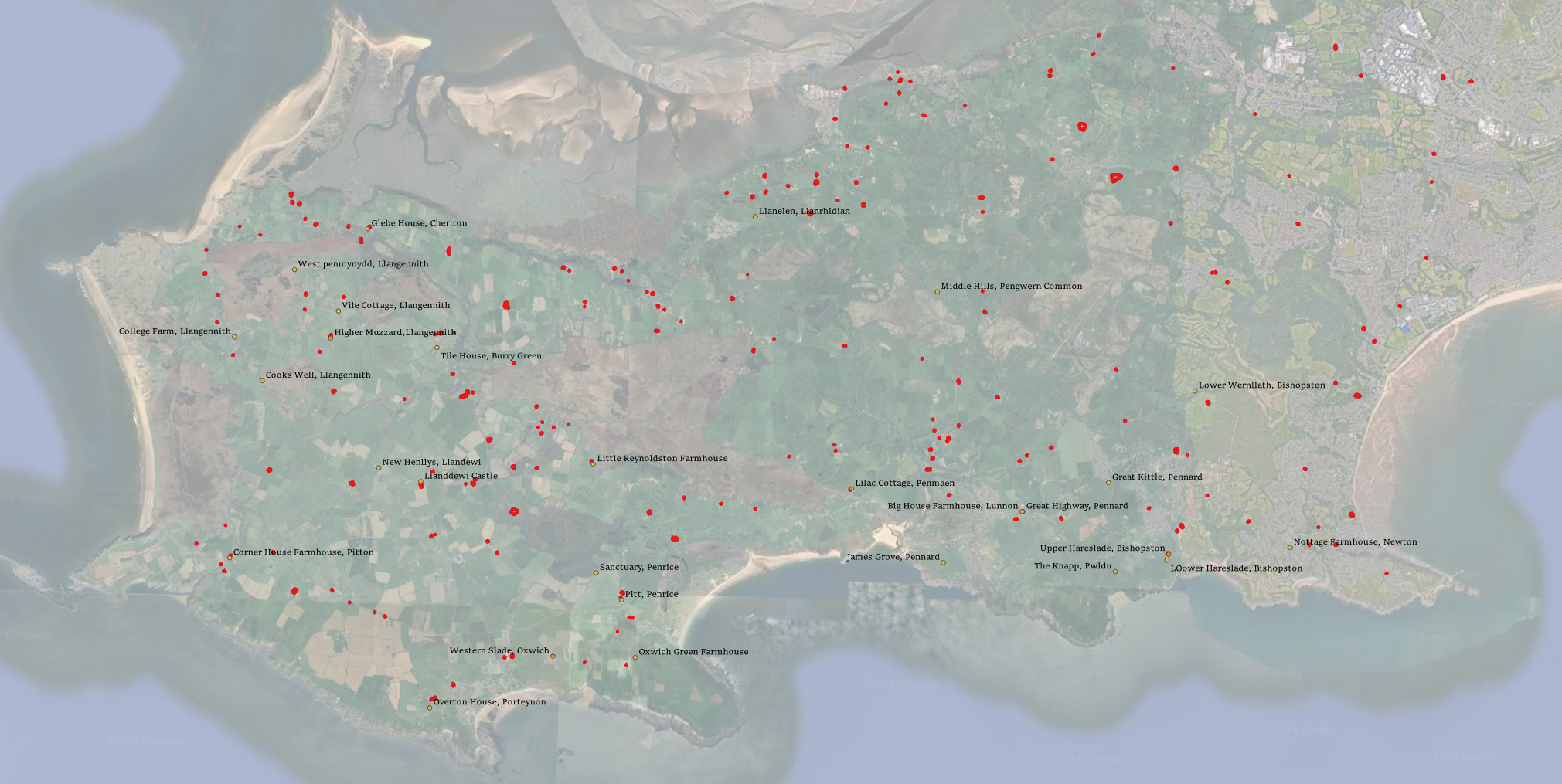

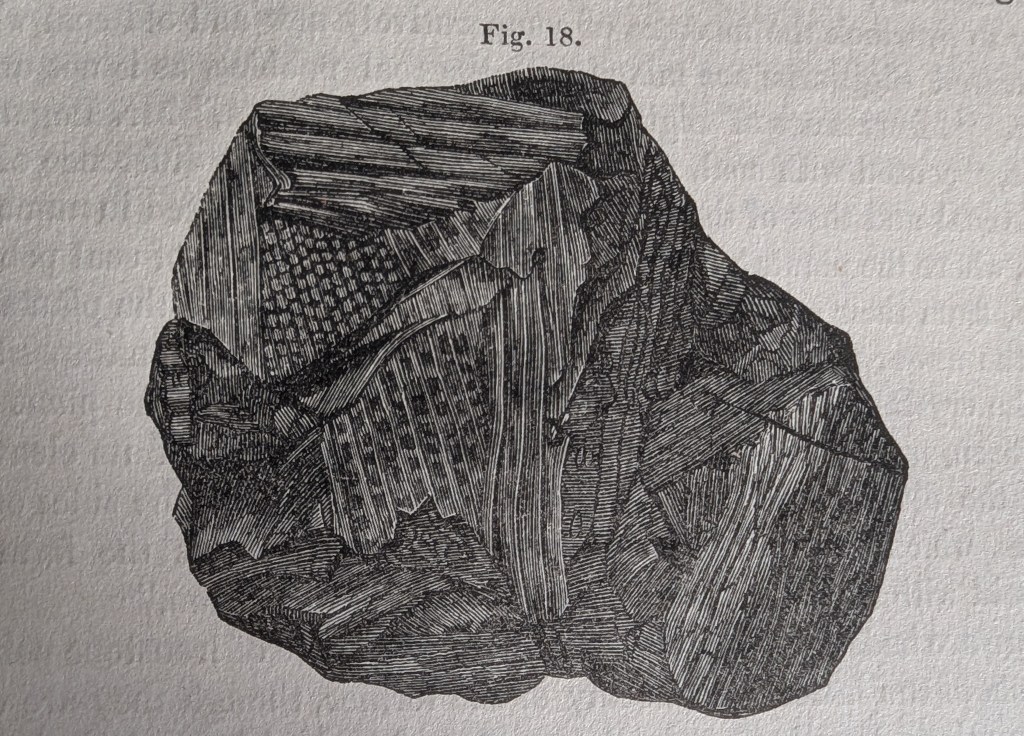

Geoheritage is now becoming a broader term for our geographical and geological features that have significant scientific, educational, cultural, or aesthetic value. Swansea has an important place in the history of geological exploration and the development of the Welsh coal industry.

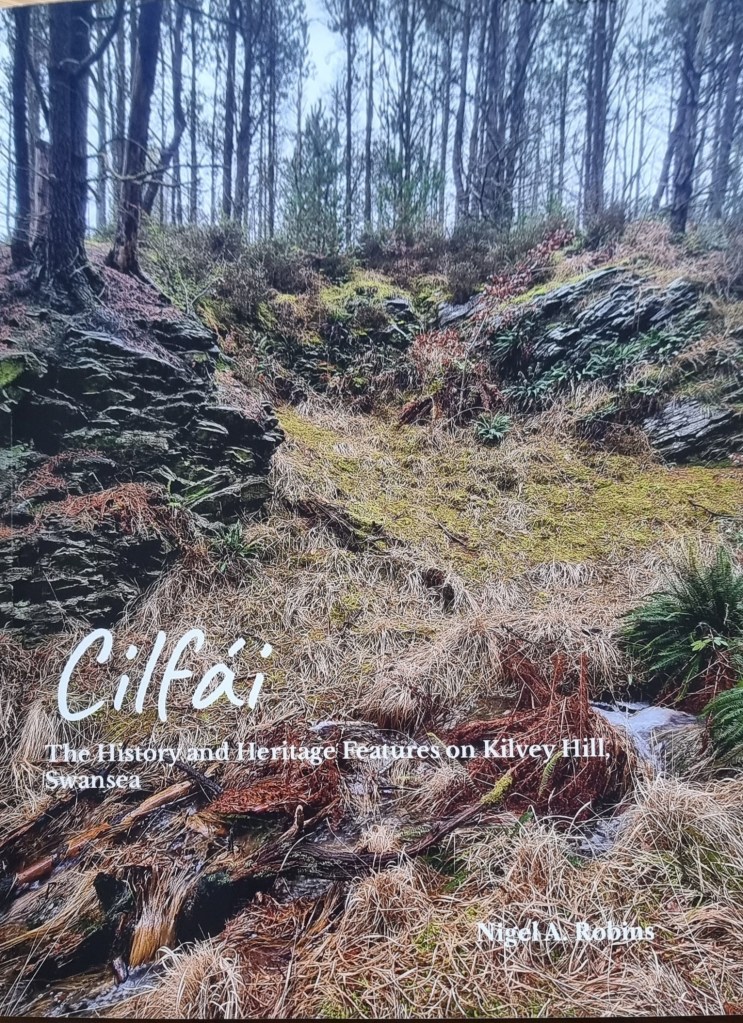

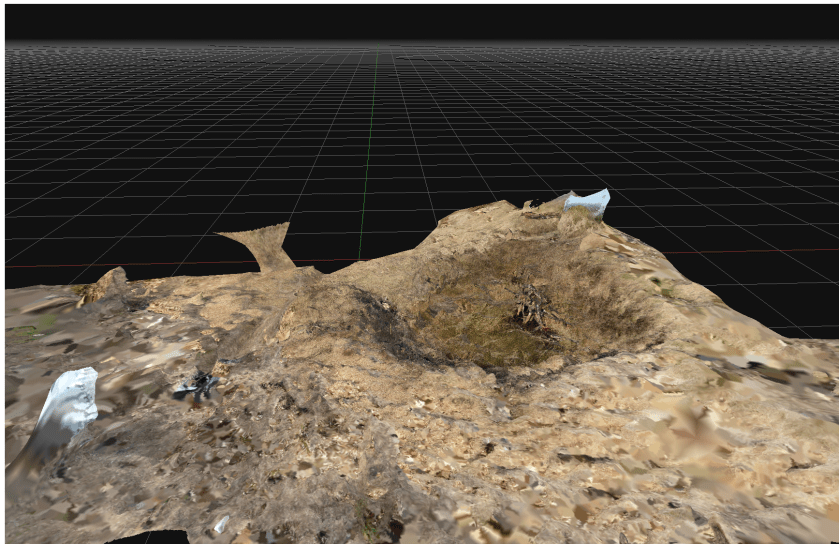

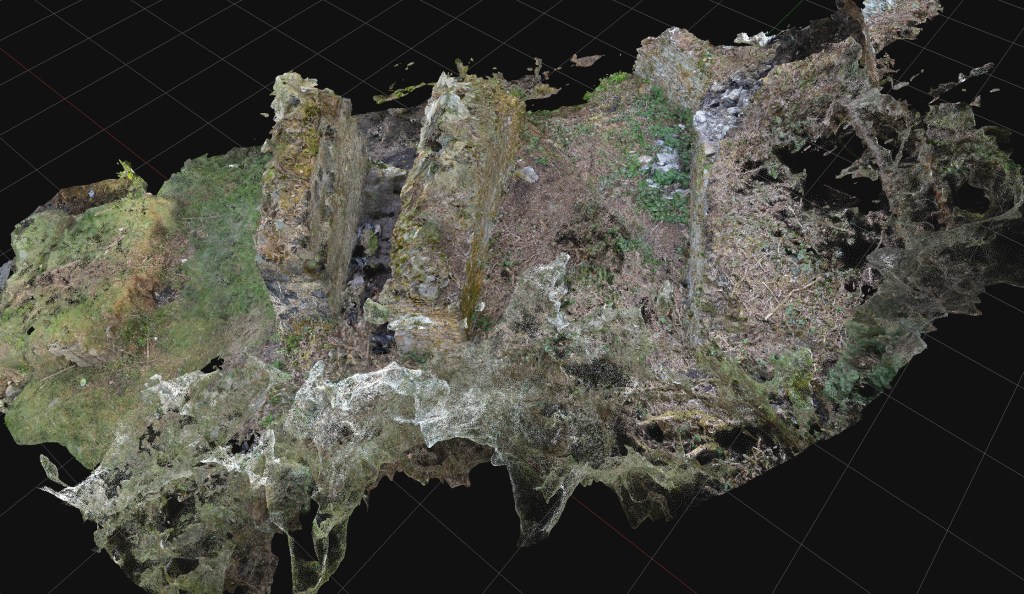

People who have participated in my many guided walks on Kilvey will already be aware of the value of the Kilvey Geoheritage sites and the contribution they make to the Biodiversity and Geodiversity of Swansea.

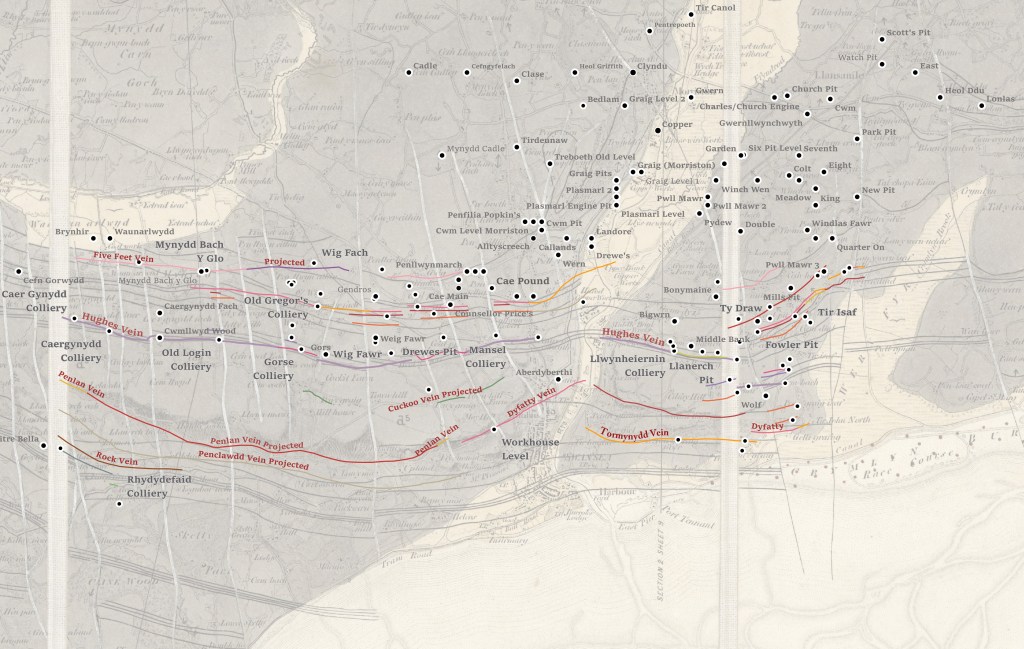

Globally, October is a month of celebrating and recognising the importance of the rocks and landscape underneath our feet. Swansea has more than most towns to be mindful of, as it is built on over a thousand years of coal mining history.

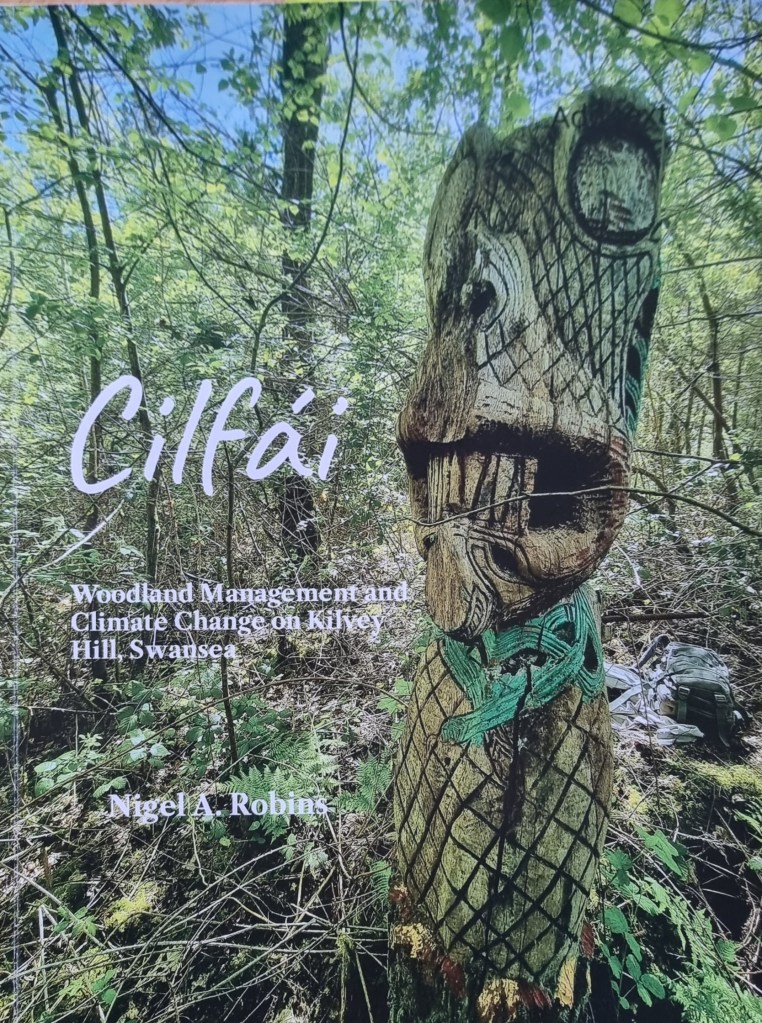

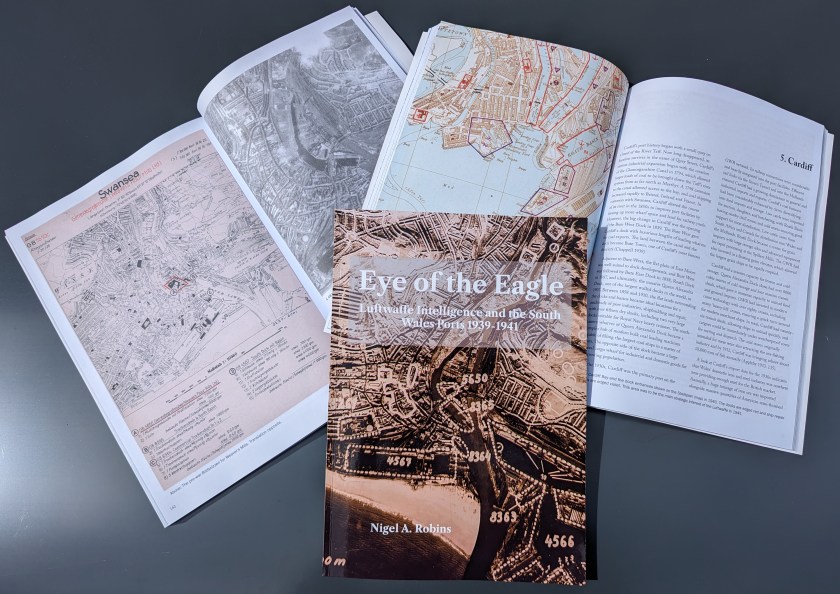

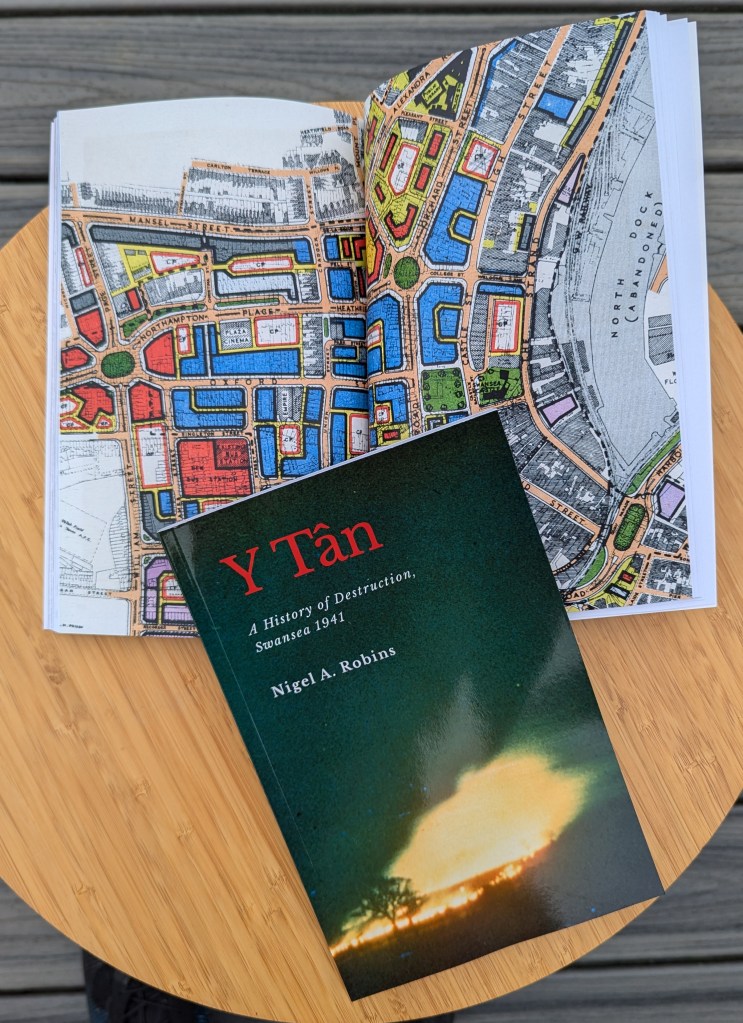

Following on from my recent book on Foxhole and the history of Swansea Coal, I’ll be giving a few guided walks and talks on broader aspects of Swansea’s incredible Geoheritage and Geodiversity.

On 4 October, I’ll be talking about the history of Swansea coal and the special place Foxhole on Kilvey has in the history of Welsh coal mining. My talk will be at Swansea Museum as part of the RISW and the Historical Association’s History Day 2025. I’ll also have copies of the Foxhole history book at a discounted price.

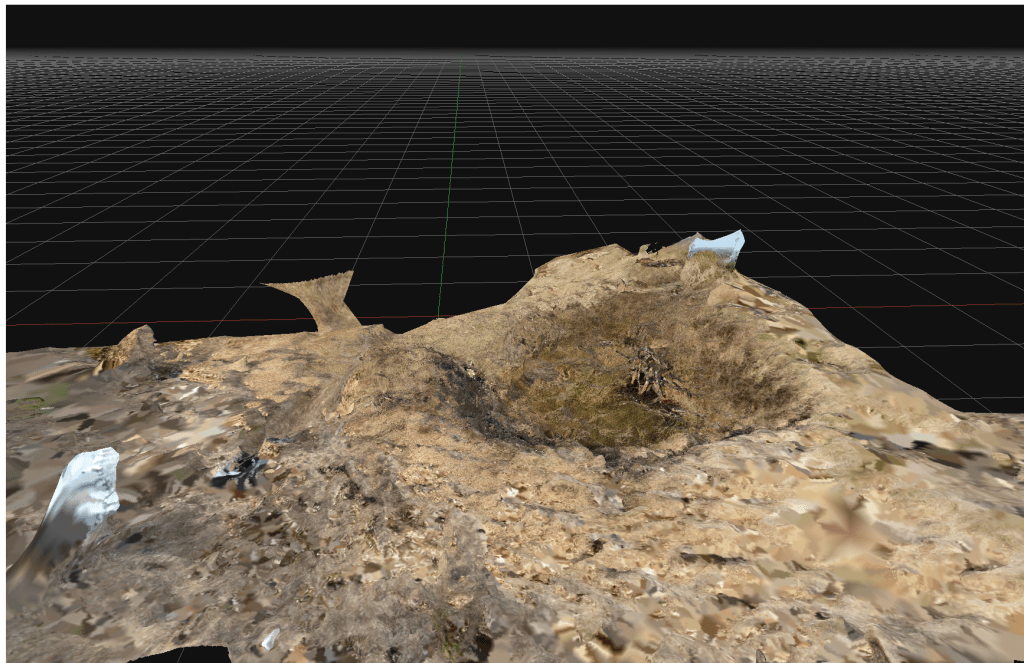

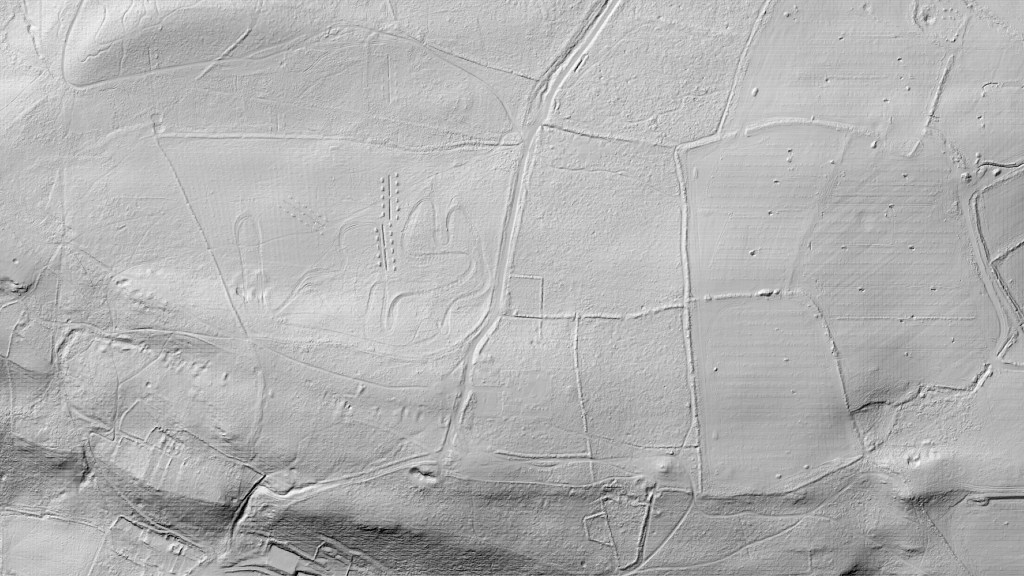

On 6 October, as part of UNESCO’s # InternationalGeodiversityDay, I’ll be leading a walk around the geological features of Kilvey Hill and explaining the unique place in Swansea’s history that Kilvey holds. The geological features of Kilvey have long been regarded as obscured or destroyed, but many have survived against all odds. Come with me and walk the land that was explored by Geology’s most famous local coal pioneers, William Logan and Henry De la Beche. Tickets will be available shortly. I’ll advertise them via Facebook and Eventbrite.

On 8 October, I’ll be at the Friends of Penllergare monthly meeting at Llewellyn Hall in Penllergaer. I’ll be talking about ‘Penllergare, Henry De la Beche, and early Geology in Swansea’. Lewis Weston Dillwyn was often at the centre of scientific and cultural events in Swansea. He was particularly prominent in the recognition of Swansea as a centre of research in the emerging science of Geology and the first understanding of the South Wales coalfields.

I’ll be doing a few more walks and talks throughout the month, and I’ll post here to let people know. If you want to know more contact mew for details.

I’ll also have my bookshop of all my current books in print at the History and Heritage Fair at the National Waterfront Museum on 27 September 2025.