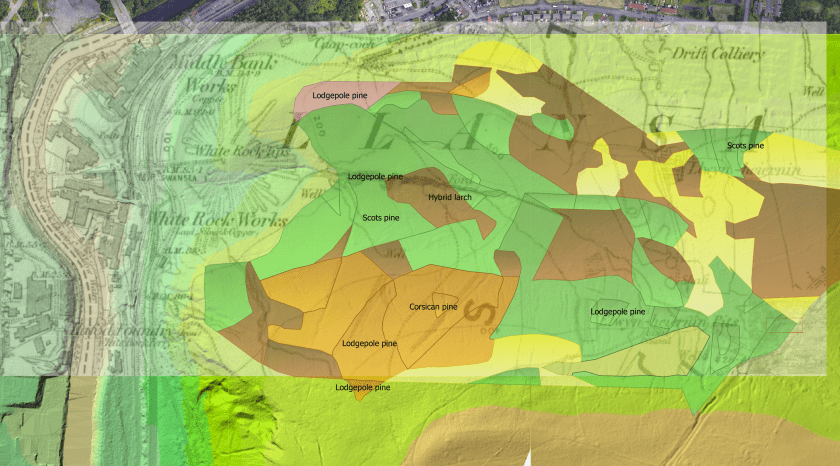

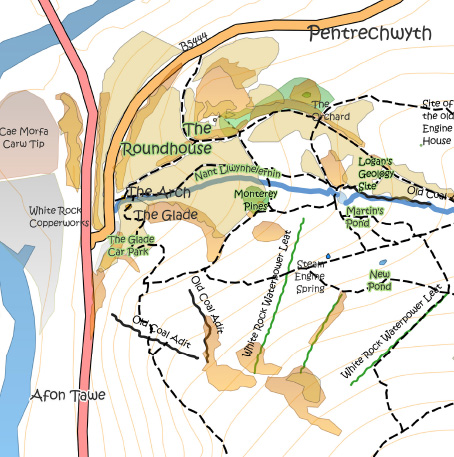

Kilvey Hill experiences frequent storms and high winds, which are a major threat to woodlands and any buildings or structures. The risk of wind damage and windthrow is expected to increase with climate change, with more frequent storms, wind speed, winter rainfall, and faster tree growth.

The projected increase in our winter rainfall is likely to increase wind risk, as rooting depth and root anchorage are both reduced in waterlogged soils. An increase in tree growth rate due to warmer temperatures is possible in areas where moisture availability is not limiting, this could increase wind risk with stands reaching a critical height earlier.

The presence of the TV and phone masts on the hill means that we know a lot about the wind speeds and weather on the hill. However, getting hold of the data is sometimes hard as it can be regarded as a ‘secret’. Anybody who walks the hill will know the signs of wind damage and constant high winds, which are now increasingly common around the year, no longer just the winter months.

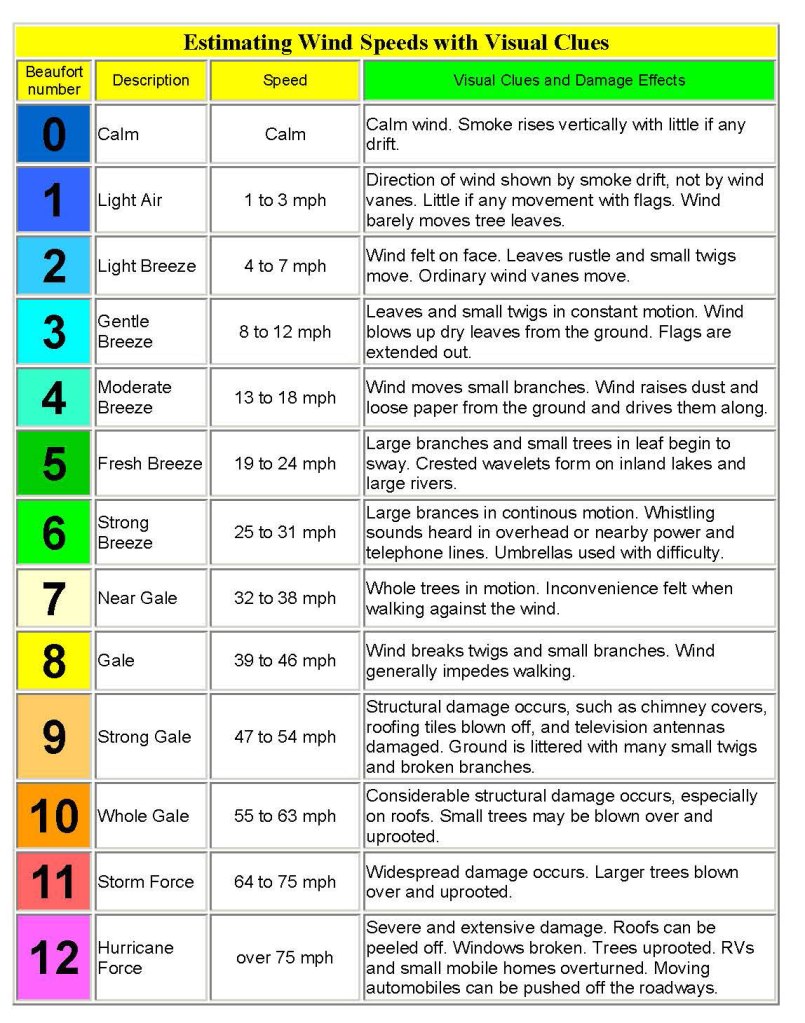

We can use the table below to assess wind speeds and damage based on the evidence we see after the storm is over. This table is based on expert fieldwork from the US Forest Service and is used all over the world. Look at the damage in the photos here and see where it is on this list…

It doesn’t matter what your viewpoints are on who or what causes climate change. The evidence is out there, and the question is how to interpret it and design for the future. It might, for instance, be an incredibly risky act for Swansea Council to risk millions of pounds (of money they apparently don’t have) on supporting a risky tourism venture on a Welsh coastal hill that is increasingly exposed to dangerous windspeeds and disruptive weather.

Those who walk the hill regularly know of the health and safety responsibility of taking walkers out on Kilvey in deteriorating or unsettled weather. We never take the risk. Would a profit-centred tourist firm be equally responsible? Would you get in cable cars and zip wires in the bad weather? Equally, how many days a year is Kilvey safe for adventure tourism? I’m not sure, but I can be confident that climate change means that the number of days of safe weather is declining as the climate changes.