One of the reasons we know so little about the abundance or distribution of bats is the general technical difficulty of surveying and recording where they live and where they hunt. Nationally, the effort to monitor the bat population is significantly bolstered by the invaluable contribution of volunteers. Their dedication, although often underappreciated, plays a crucial role in our understanding of bat populations. However, this reliance on volunteer work, while commendable, is not without its challenges. The situation is further complicated by the need for specialized equipment and training. Although bat surveys have become a regular requirement for planning permission, the surveys remain expensive and knowledge is considered commercial and rarely shared, making understanding of bat distribution even more complex. Using specialist recording equipment means the data files for bat surveys can become very large very quickly, although the advantage is that the data is available for further analysis and verification.

I trained as a bat surveyor in the Thames Valley, where University researchers waxed lyrical about the high densities of bats along the river. One warm night we went out and didn’t detect a single one. That has never happened to me on Cilfái, where bat presence can be staggering on many nights.

Bat surveys have become high cost as surveyors seek to extract as much income from the work as possible. It is unfortunate, as much needed information then becomes restricted or unshared. That greedy attitude led me to share as much as I have on the bat presence on the hill in the second Cilfái book. Cilfái: Woodland Management and Climate Change on Kilvey Hill, Swansea.

On Cilfái, I use a combination of a handheld detector and automatic recorders, which give me a sample of several nights at various locations. This lets me hear the bat calls as they hunt and analyse the recordings at home. I use the classic handbook for techniques Jon Russ wrote (Russ 2012). I use Anabat Express (or equivalent) passive bat recorders and process the data with Anabat Insight Version 2. Over time, this gives me an understanding of the ‘hotspots’ of activity across the hill. I only get snapshots of what is happening, and I cannot realistically project what I know into the overall picture of bats on the hill. That will take a few years. I can assume that our ‘Year Zero’ in 1970 had no bat presence and that everything I see and hear in 2023 is the product of fifty years of recovery. However, realistically, the woodland only began its recovery in the mid-1990s.

The hotspots on the hill are where the food is. Generally, these are the open spaces where previous burning or wind damage has opened up the forest canopy and allowed a wider range of native plants to prosper. Some of these open spots are also good for birdlife. On a warm autumn evening, the air in the hotspots is thick, and flying insects attract the bats. I have evidence of a large presence of Common Pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pipistrellus) and Noctule (Nyctalus noctula). It is possible that hidden in my recordings is some evidence of the Brown long-eared bat (Plecotus auritus), only further data collection will confirm.

Although I can track and monitor activity, it remains immensely difficult to understand hibernation and roosting sites. I am slowly building up a library of bat presence data across the hill.

Russ, John. 2012. British Bat Calls: A Guide to Species Identification (Exeter: Pelagic).

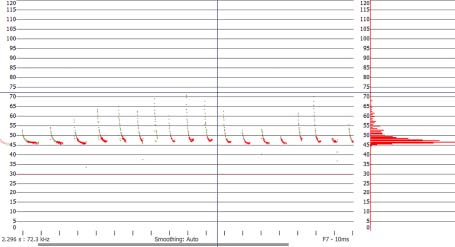

Below: Although it looks a bit technical, it is the nature of bat survey work that we prepare this kind of evidence. The land above Foxhole and the Glade is very busy with bats and clearance of trees will definitely cause problems for the population that has re-established up there. On the night this recording was made I had hundreds of similar records. You can see more evidence in the Cilfái book.

This is a recording of a Common pippistrelle hunting on the woodland edge above Foxhole in September 2023. Temperature above 20 Celsius (Analook F7) compressed with split-screen option Cycles, showing the characteristic call shape of a hunting pippistrelle.

Below: Me bat surveying on the threatened land above Foxhole September 2023