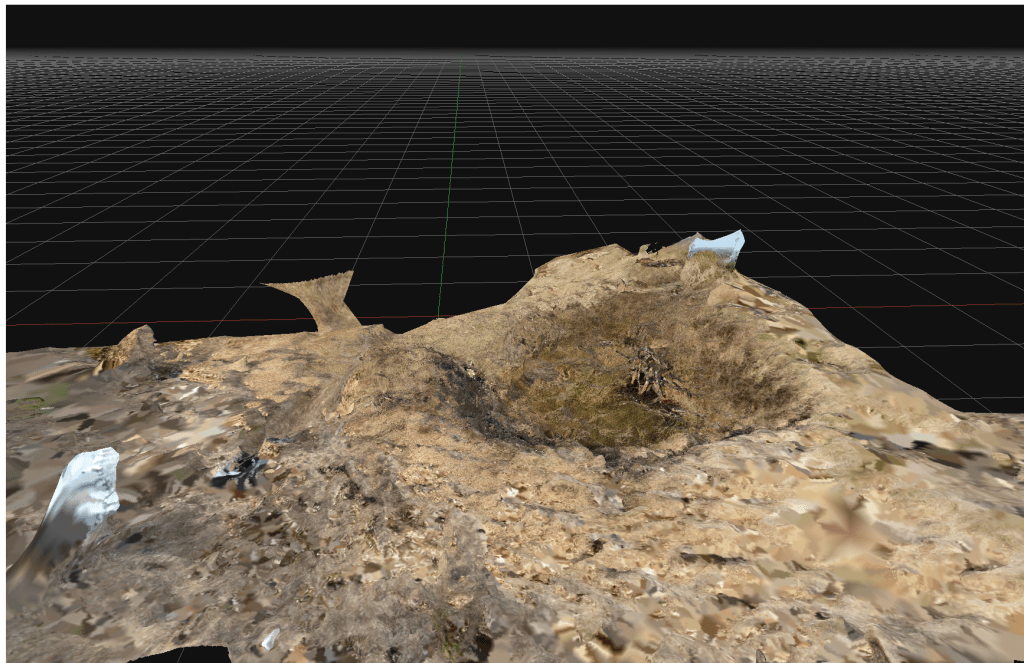

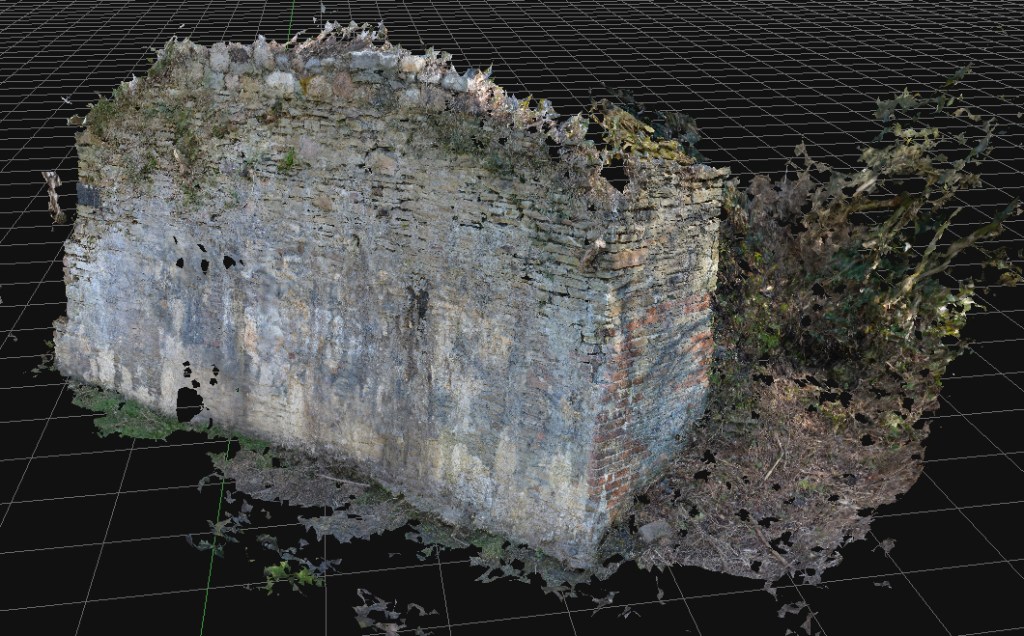

The rapid development and delivery of this project is almost complete. The proof of concept of quick and cheap photogrammetry is complete, and we explored various features of various sizes. Budget constraints in the broader London-based programme meant that the planned exploitation phase won’t take place there. The plan was to explore some large, immoveable sculptures and statues at risk of damage by surrounding building renovation. Instead, I’ll work in South Wales on a series of local history and geography projects.

Costs were remarkably low (which we believed they would be). It is satisfying to use new technologies to reduce costs and fight against the gradual cost inflation and scope creep of using these types of technologies in small history or geography projects. In researching the business case for this, I learned of several local authority projects where high costs for archaeological surveys, often incorporating expensive drone surveys and extraordinary labour costs, skewed project delivery budgets almost to the cancellation of the projects. I experienced the same issues working on the restoration of the Palace of Westminster, where incredible finances and resources were expended on expensive lidar and photogrammetry products that were who;;y unsuitable for the problems and frequently misled managers into thinking that such products were essential elements of the restoration at RIBA Stages 1 and 2 .

For many projects in restoration and landscape, there has been a tendency to overemphasise gee-whiz graphics at the cost of scholarly historical analysis. The project here puts the technology back where it belongs, in the background of support for investigation and analysis.

Costs are kept low by avoiding the use of drone technologies, using older and previously-used professional cameras bought cheaply on Ebay, and new software costing a few hundred Euros.

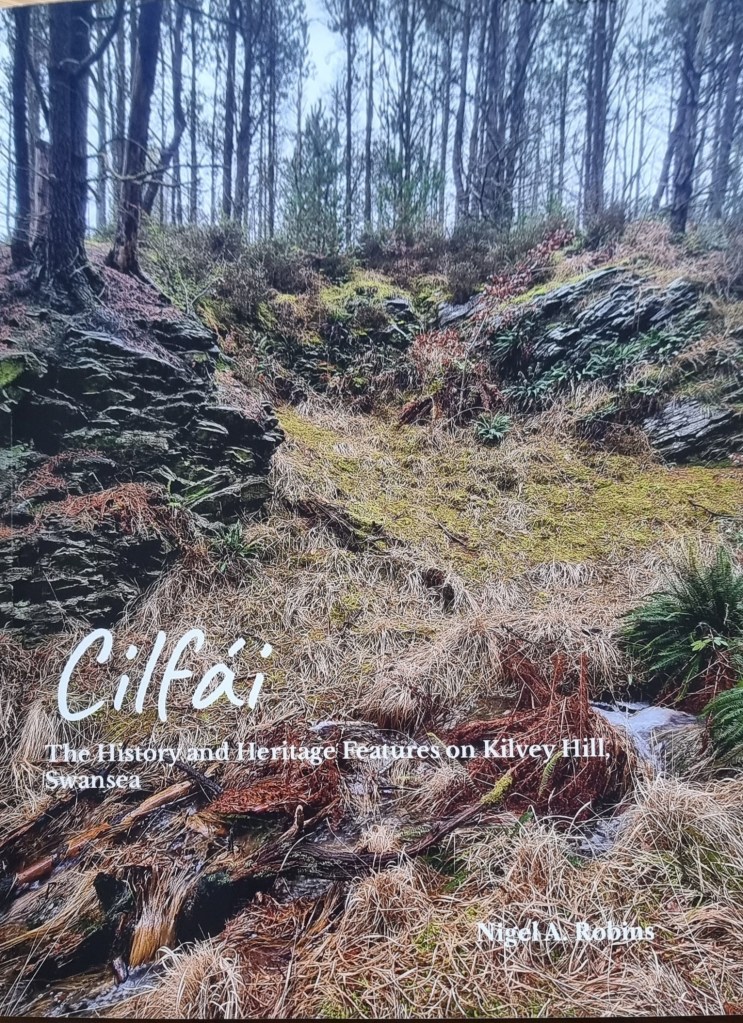

The next steps are researching the history of coal industry structures in the valley, followed by some investigation of some World War Two remains on Cilfái.