Castle Gardens appears to be unlovely and unloved. I know it is the target of a proposed refurbishment ‘after consultation’. The plan I saw promises small (cheap) changes.

I grew up wandering around the original Castle Gardens in the 1960s. Chasing the army of pigeons that lived on the roofs of the Sidney Heath’s buildings. It was full of green spaces and the Sidney Heath fountain, and the covered area was always full of (to me) old men sitting and drinking. The fountain seems to now be in the gardens in Singleton.

The open space originated as a ‘Garden of Rest’ site after the Blitz. (Evans 2019). It eventually (after the inevitable Swansea Council arguments!) became the open space of some grass, some paths and the fountain, which stayed until 1990 when it was obliterated for the ghastly makeover we see today.

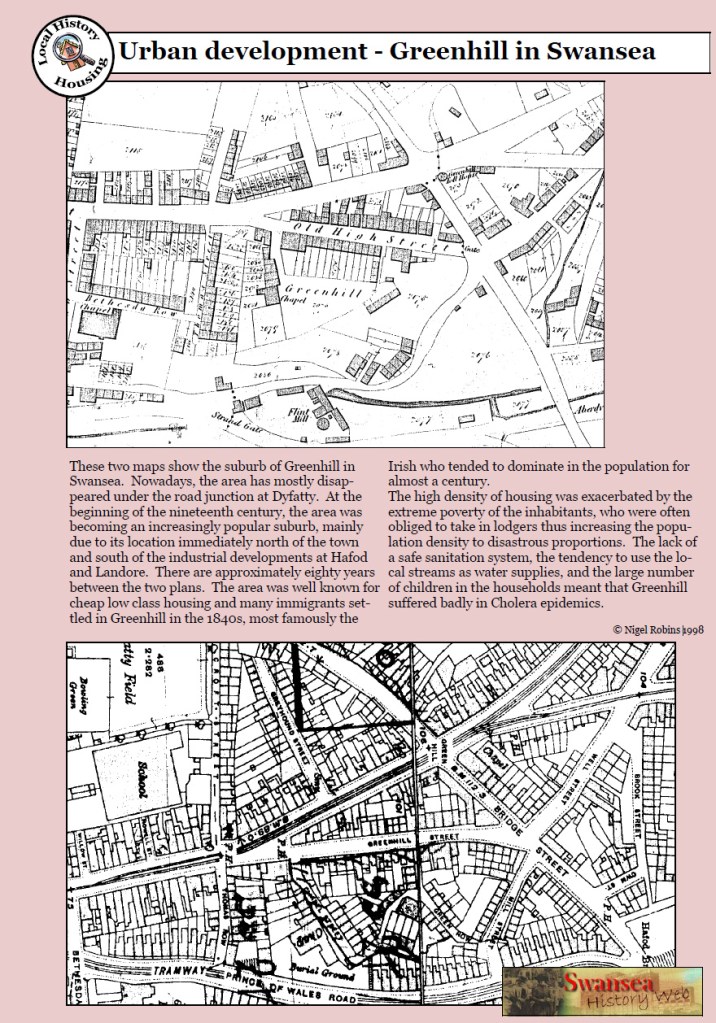

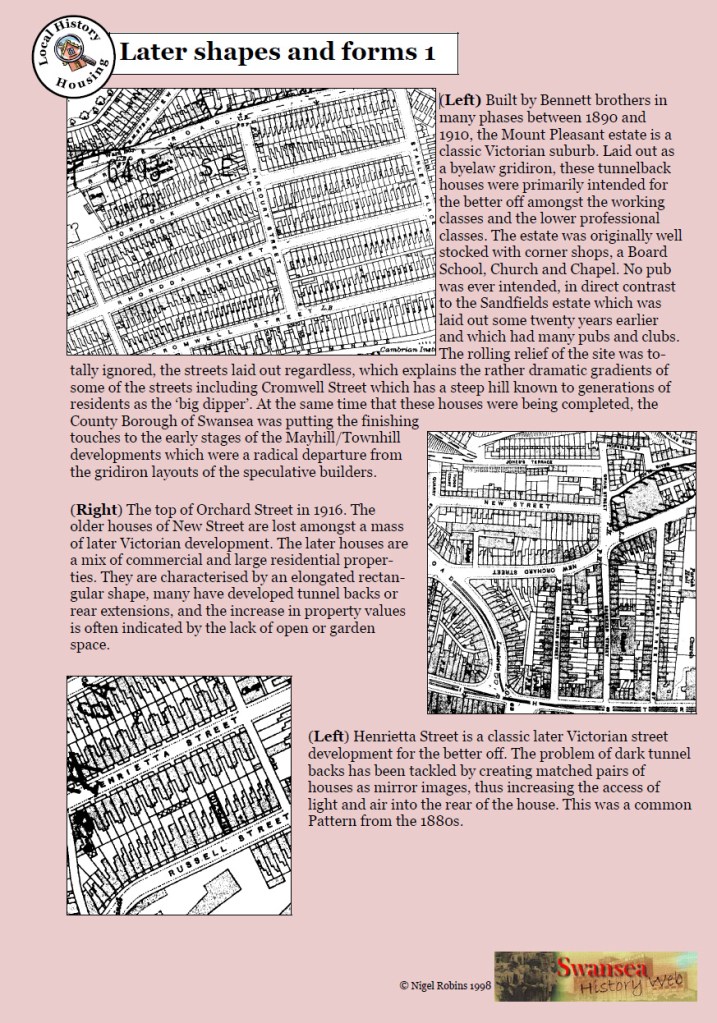

The plot of land is fascinating. It was the site of the famous Ben Evans store and, before that, the Plas manor house. As one of the most significant urban areas of the medieval town, it may be that significant archaeology lies underneath the northern side close to where the Plas and Temple Street were.

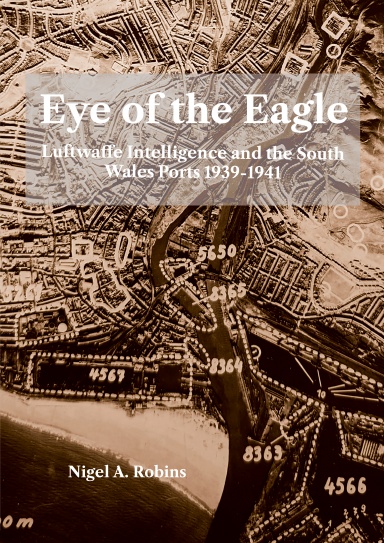

In my latest research on the Blitz, the plot is helpful to study the impact of incendiaries on the wider town and it’s become a case study in my next book.

Understanding the site that once held Ben Evans entails delving back into the past to look for the Plas manor house and the rebuilding of Cae Bailey Street between 1840 and 1850. The maps are poor, but we do have a fantastic model of the area made in the 1840s, which is now in Swansea Museum, and Gerald Gabb has examined all the paintings and prints in his books (Gabb 2019: 199–207).

I’m digitising the various stages of buildings in the Castle Gardens site as part of the background for understanding the Swansea fire catastrophe of February 1941 (Alban 1994). I’m lucky in that there is a detailed survey of the area from 1852, which is the basis for establishing the area that eventually became Ben Evans in the 1890s.

Alban, J.R. 1994. The Three Nights’ Blitz: Select Contemporary Reports Relating to Swansea’s Air Raids of February 1941, Studies in Swansea’s History, 3 (Swansea: City of Swansea)

Evans, Dinah. 2019. A New, Even Better, Abertawe: Rebuilding Swansea 1941-1961 (Swansea: West Glamorgan Archive Service)

Gabb, Gerald. 2019. Swansea and Its History Volume II: The Riverside Town (Swansea: Privately published)