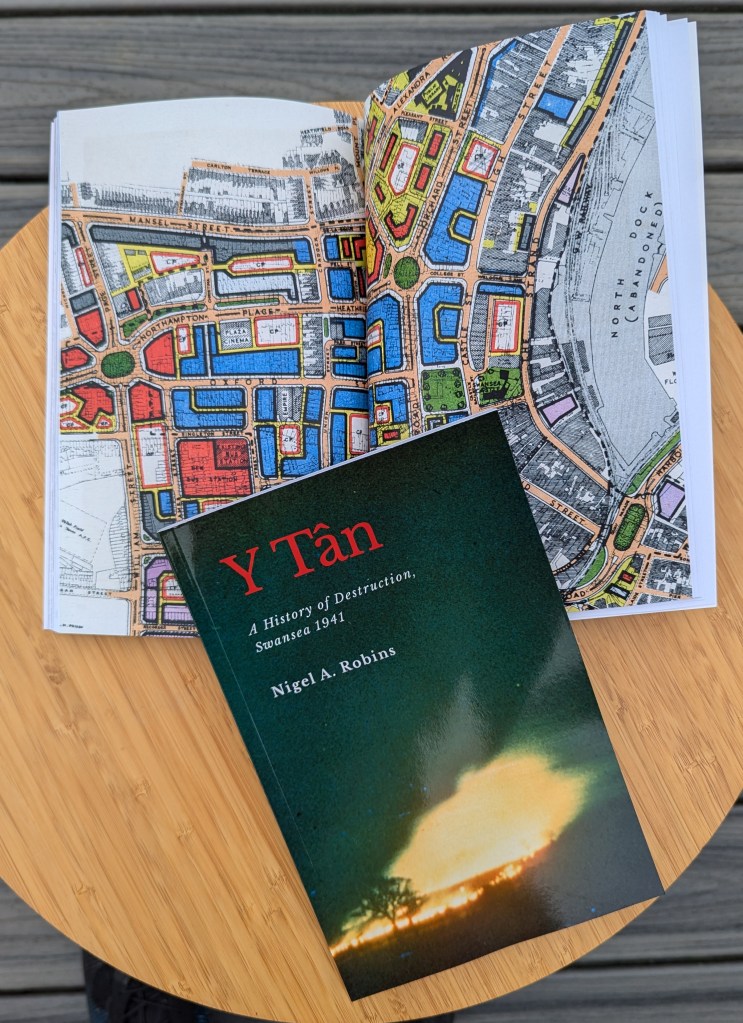

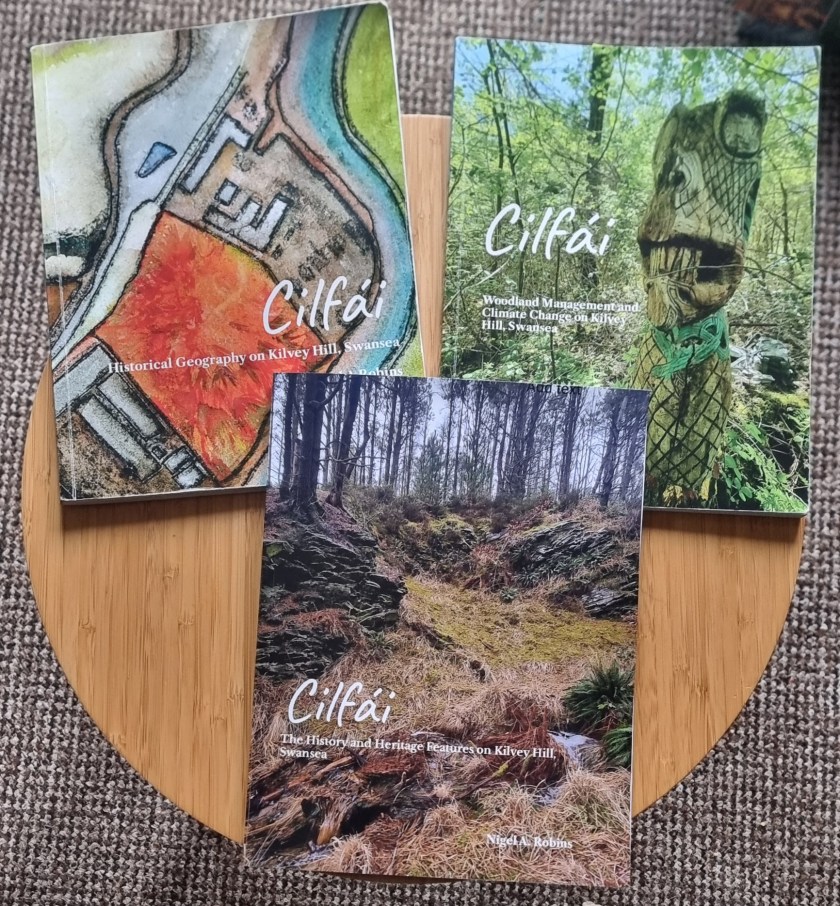

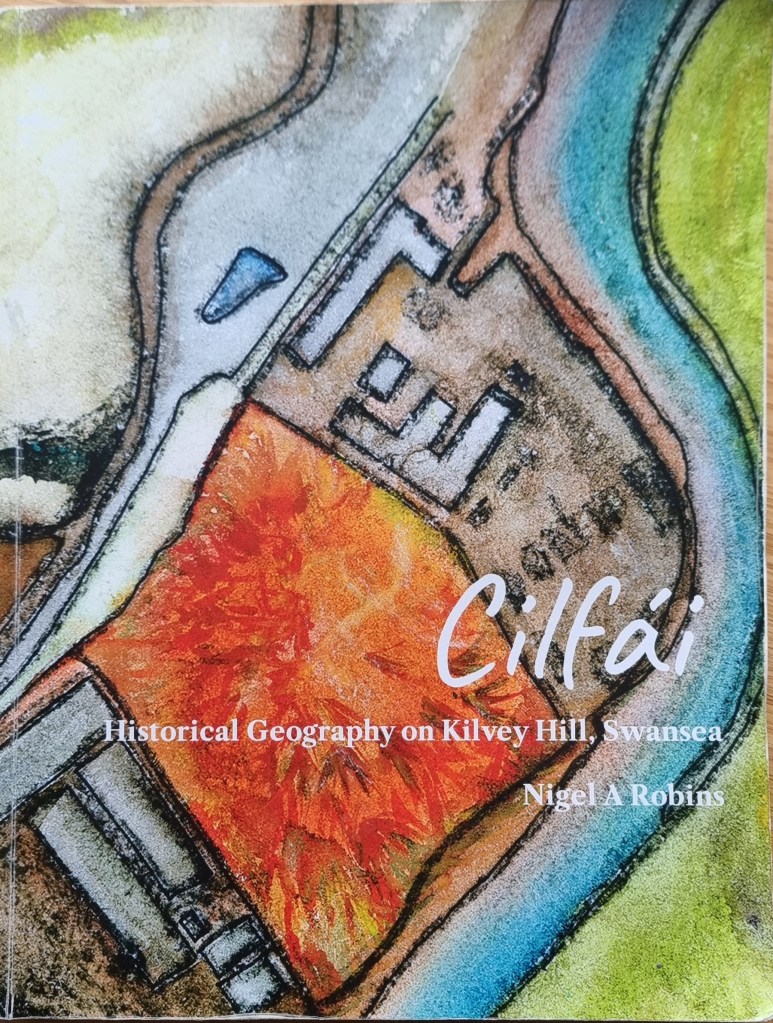

This has now been reissued as a 2025 Second Edition with some updates, minor amendments and some new illustrations. I’ve also updated the copyright and EU product compliance details.

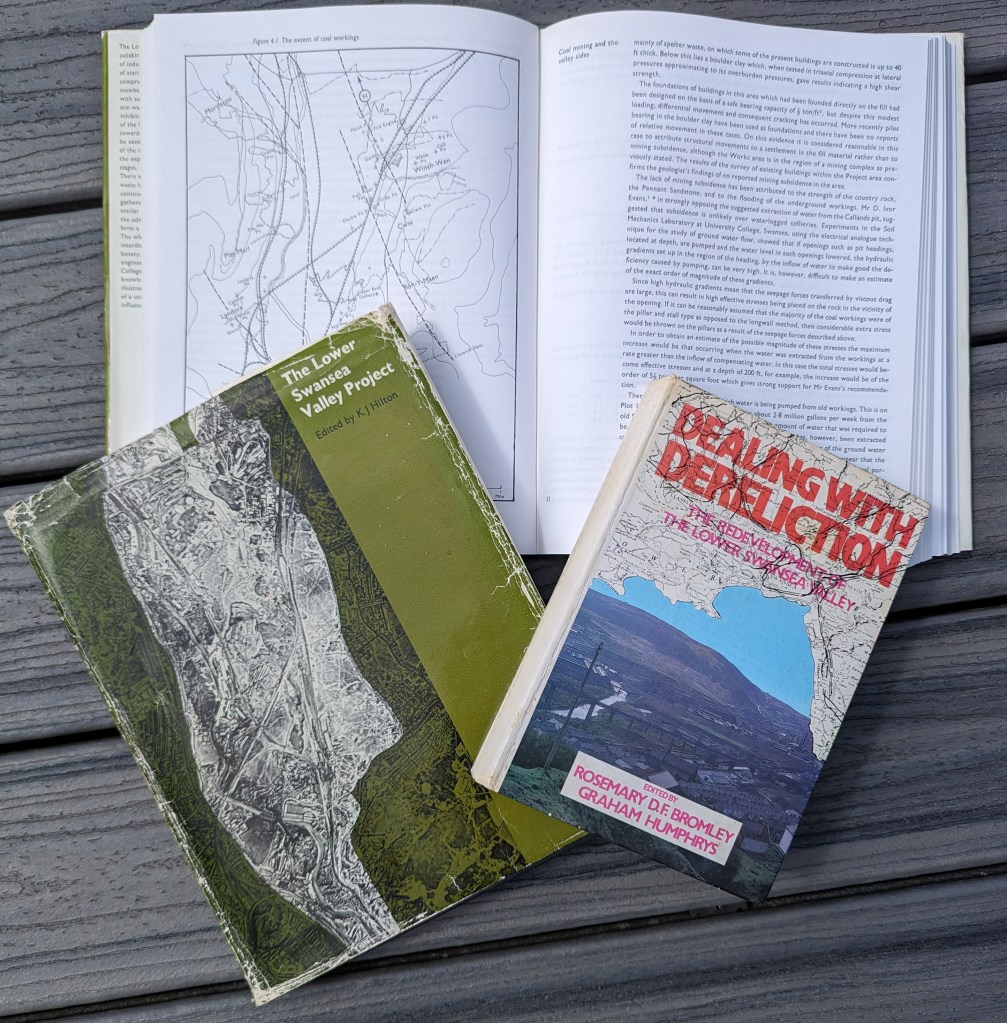

This study has been heavily reliant on past teaching notes and lessons learned from students’ questions and discussions over many years. I am indebted to all of them. Grateful thanks to the staff of West Glamorgan Archives Service and the archivists at the British Geological Survey in Keyworth who allowed me to spend time with William Logan’s original notebooks. The help of experts such as Dr John Alban and Gerald Gabb has always been beyond value and they have helped me as a sounding board and unlocking further fields of expertise which ave been so valuable. The contributions and discussions with my oldest friend John Andrew on geology and the rocks of Townhill and Kilvey have been particularly inspiring. John passed away in August 2024 and I miss his help and support terribly.

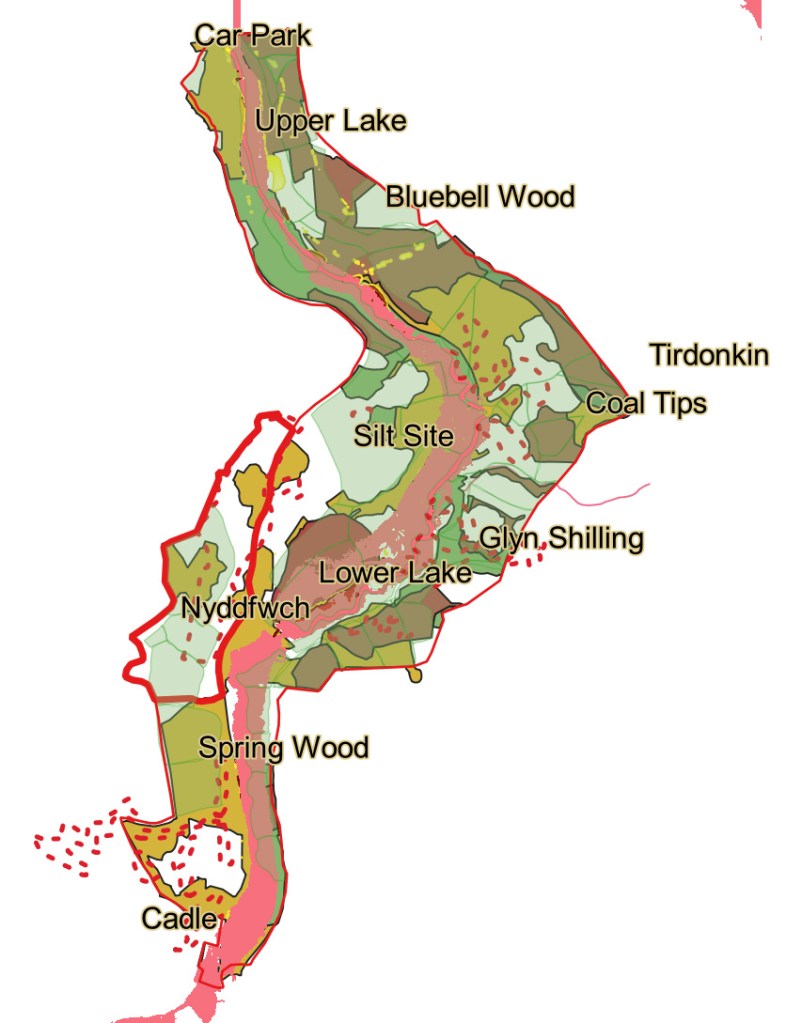

I must also thank the staff and colleagues at Coed Cadw/Woodland Trust who, unwittingly perhaps, spurred me on to re-explore Kilvey some thirty years after I last surveyed the land in the late 1980s. All the modern mapping was completed using the open-source QGIS application which has become a central tool as a landscape historian over the past ten years. Finally, I must mention the help and support of Kilvey Woodland Volunteers. Without the passion and commitment of the volunteer body over many years, I doubt that Kilvey would be the special place it has become. As I write this, Kilvey is under more threats from the local council and developers, and I hope this little book records a few milestones in the ongoing Kilvey story rather than an ending.

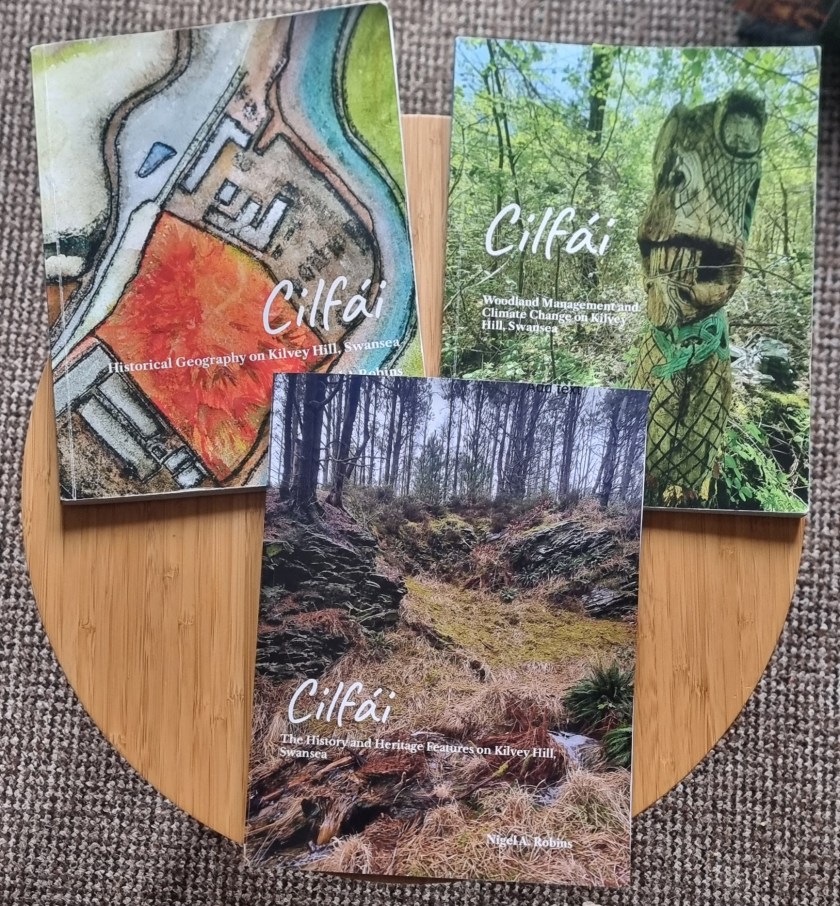

The first edition of Cilfái was remarkably successful. The aim was to fill a gap in knowledge about the Hill in the constant challenge to take care of it in the face of threats of irreversible destruction from tourist developments and an uncaring local authority. There are now many more local environmental and residents groups aware of the current value of the land and the potential loss Swansea faces if the destruction begins. This book was the first of the Cilfái trilogy, the second book covered Woodland Management and Climate Change, and the third book covered the heritage features on the hill. This book was rushed into print to address claims from the Local Authority that there was ‘not much up there’. Since 2023, I’ve taken hundreds of people on walks to view the biodiversity, history, and heritage of Cilfái, and I’ve packed out numerous community centres and halls to talk about the history. Hundreds of people have been converted to the value of the landscape we may lose.