Nigel A Robins (2022) Heritage digital asset management data requirements. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.6912783. https://zenodo.org/records/6912783

This is my work list for the Heritage Data Requirements Strategy for the Palace of Westminster Restoration and Repair. This is an outline of the work, most of which was completed. This evolved into a fairly detailed Heritage AIM, although the final execution of any plan was never completed.

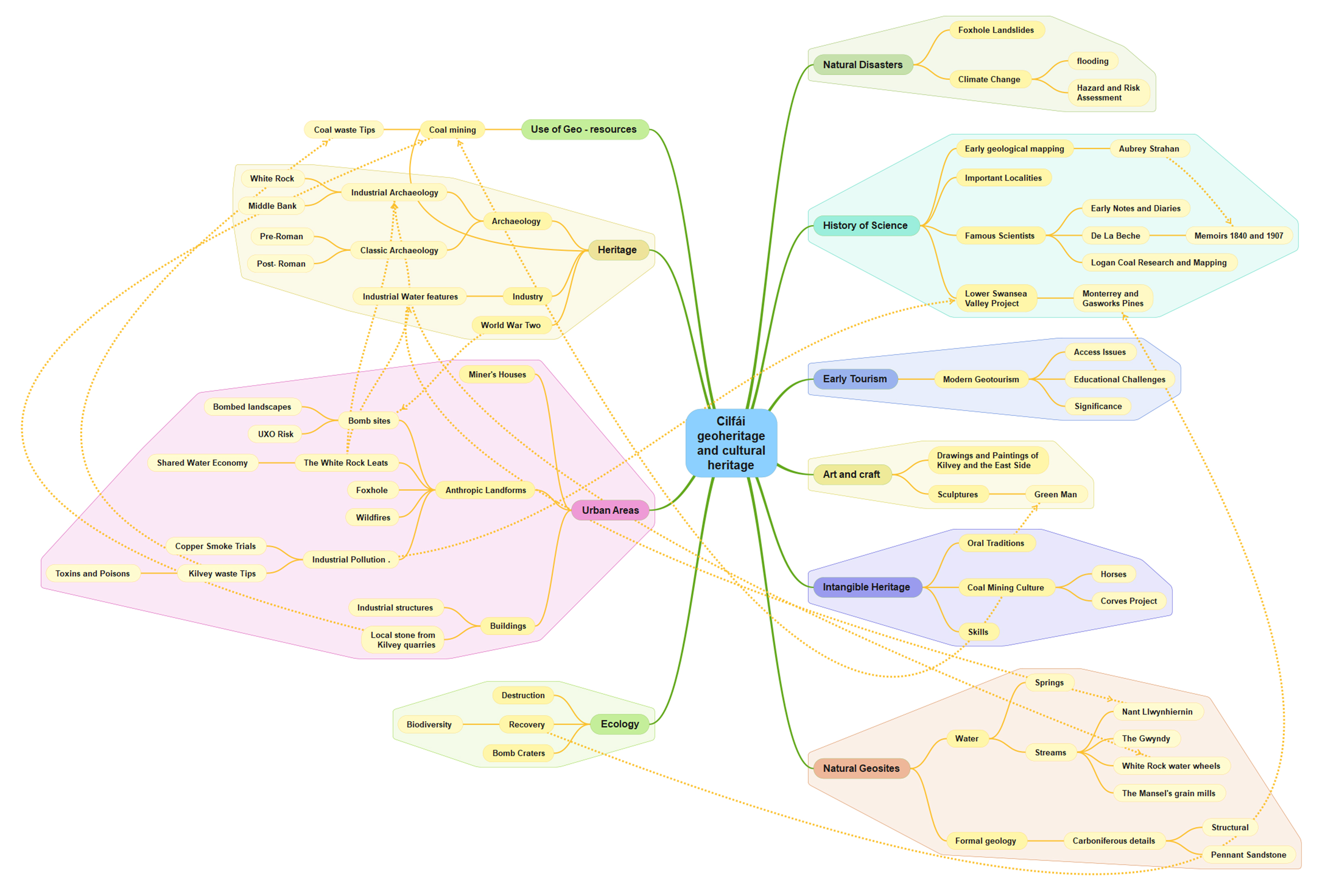

This script provided the basis for several other projects that were perhaps more successful, or at least easier to work alongside.

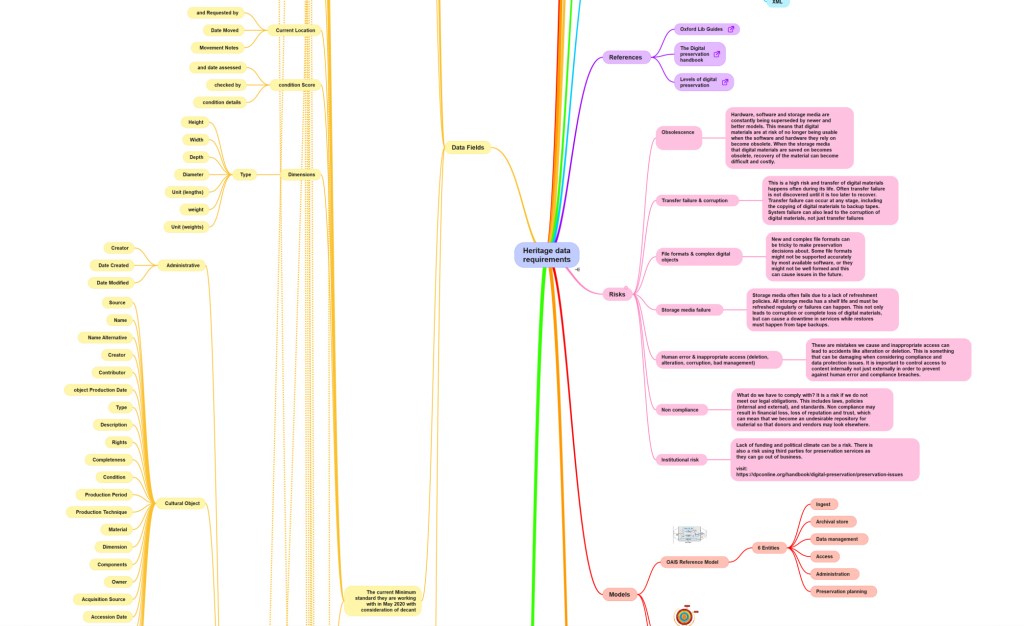

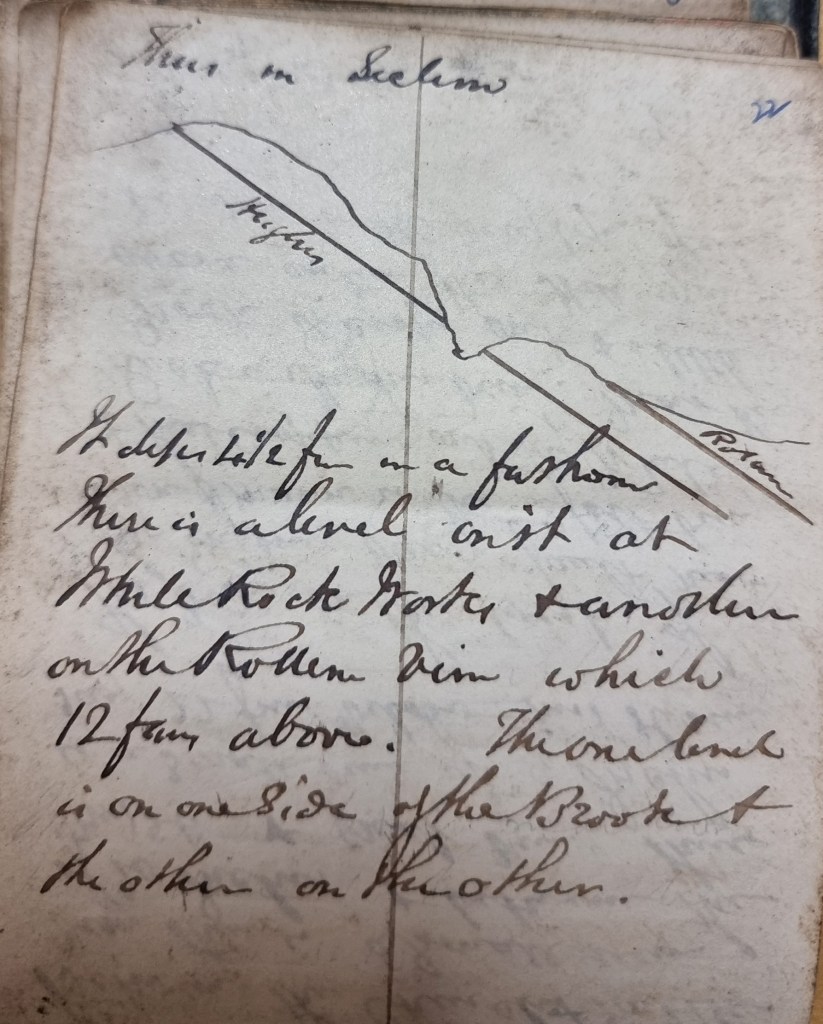

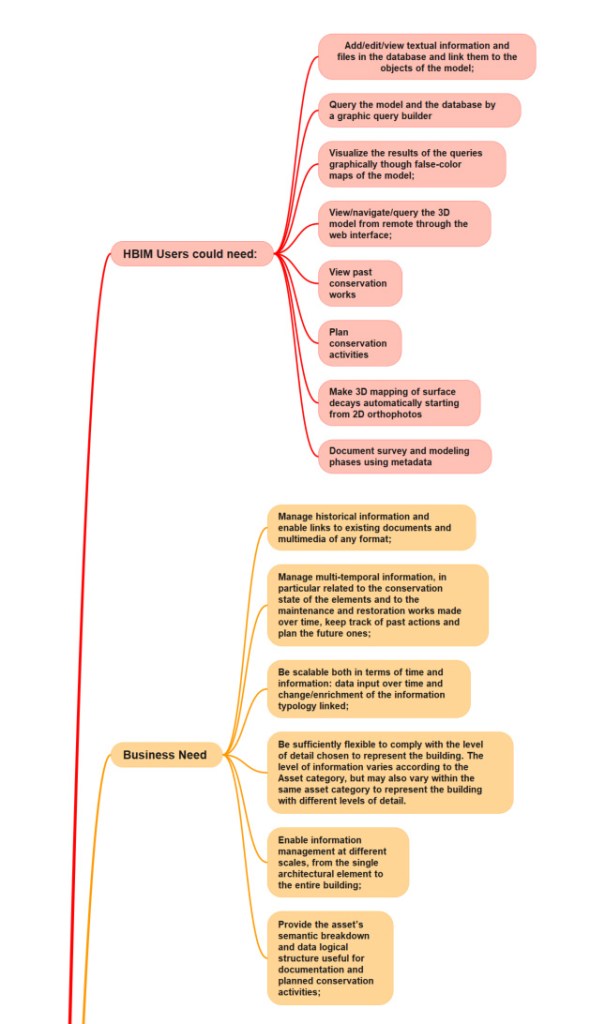

Analysing the ‘as-is’ situation, via intensive and sometimes exacting canvassing and fieldwork, highlighted many problems with current cataloguing standards and the extent of deployment of systems and staff capabilities (the current minimum inventory standard of core information for Axiell Emu). All very difficult challenges. The original data fields (Data fields on the card box system) were too focused on legacy data and staff skills from earlier decades. The recognition of what HBIM users could need (HBIM Users could need, Business Need) was difficult for conservation staff who were worried about job security.

After the BA fieldwork, some alternative schemes were mooted (New Scheme?). A certain amount of tension emerged between current users of Spectrum 5.0 and the IT managers (who knew very little about Heritage CMS). A decomposition of Spectrum 5.0 was essential to highlight exactly where issues with data security and staff attitudes were likely to clash. At this point, I thought it advisable to introduce BIM elements (Semantic Information Levels). This was an attempt to establish consensus on what was needed. IT staff were poorly grounded in the realities of building conservation and found it challenging to understand concepts such as Levels of Detail, including discussions of scale.

Continued canvassing and fieldwork led to identification of a pick list of data fields (Data Fields). Decomposition of data fields resulted in a scratch list of risks (Risks) which proved pleasingly accurate when I was able to discuss with other institutions and organisations.

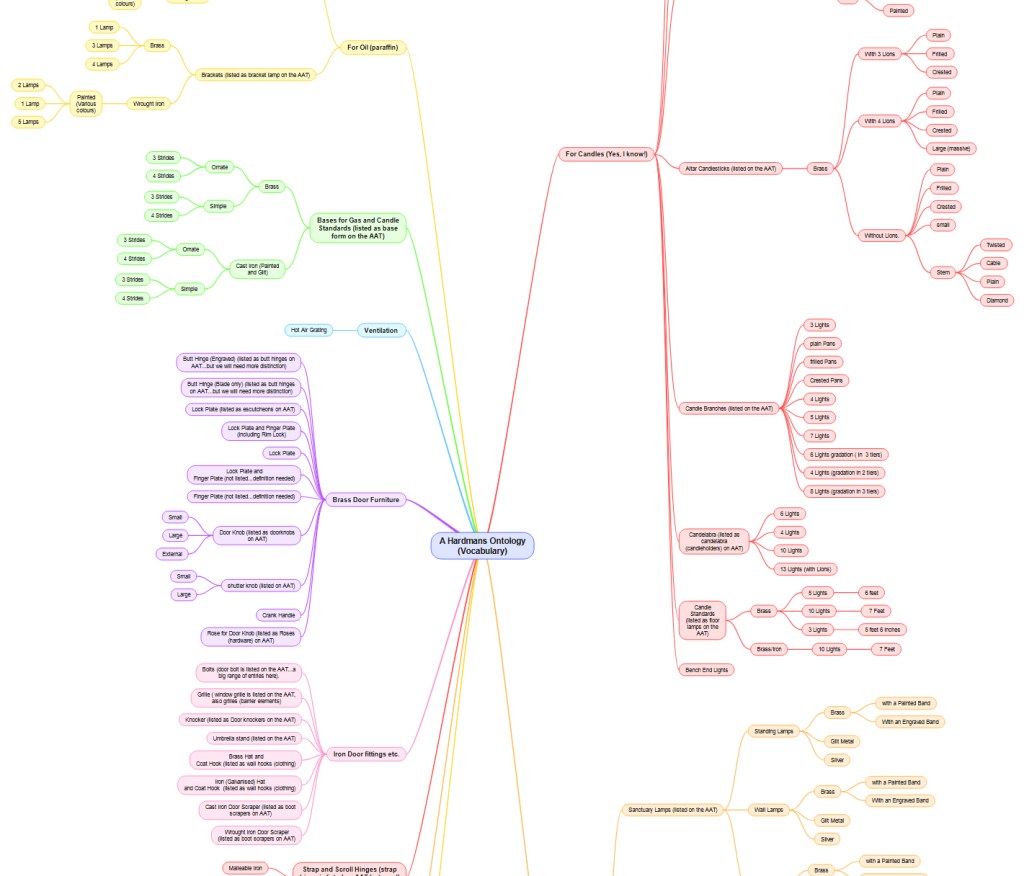

Metadata proved a challenge as agreeing a helpful starter list was remarkably difficult. Again, much of this was due to a lack of experience amongst IT staff who remained blissfully unaware of FISH (https://heritage-standards.org.uk/) or Getty AAT.

Finally, Use Cases were completed (Potential Use Cases). The initial work was via a set of personas, again some of these concepts were novel to staff and great care had to be taken to introduce concepts gradually. The detailed use cases were assembled using conventional requirements gathering and design definition processes (via BABOK sec. 7 etc.).