In December 2022, several senior councillors and council planning staff met in the Swansea Environment Centre with a group of concerned local people about the proposed Skyline developments on Kilvey Hill. The meeting had been prompted by the leak of information concerning a clandestine operation by Council staff to assemble a portfolio of landholdings on Kilvey Hill, which was to be leased to the Skyline investment company. Some of the land was not owned by the Council, and the authority had made strenuous efforts to obtain the land, not least because key parts of the Skyline development were planned to be built on the top of the Hill. The Council presented a series of rather mendacious arguments and ‘mistruths’ describing why they think they should acquire the land for no charge.

The meeting kickstarted a series of legal events about the unowned land and the broader picture of how the Council were dealing with the entire hill. Controversies over legal entitlement and determining a 999-year lease originally made to the Forestry Commission in 1970 abounded. The legal melee was made even worse by revelations that the hill was a designated quiet area, that there had been inconsistencies in how open access land and footpaths were being managed and a further deterioration in relationships between the Labour Council and local residents. If indeed, such a thing was possible.

The Council Leader(Robert Stewart) promised to ‘share as much as we know’ about the scheme. However, it turned out that he didn’t actually know too much, although he was obviously unwilling (and unable) to share what he did know about dealings inside the Welsh Government, an unfathomable business plan, and millions of pounds of public money being donated to a private-sector tourism venture.

I thought the meeting went as well as could be expected. Which is to say it didn’t go too well. How could it have when the questions (the good, bad, and ridiculous) were batted away with a flourish of ‘it’s too early for that’ or ‘we don’t know yet’. As the atmosphere deteriorated, Stewart descended into the understandable tactic of making stuff up, such as saying a council ecologist had been appointed, all pathways had been comprehensively mapped, and Ecological Impact Analysis had been completed, and a gradual awareness among the audience that this wasn’t a proposal in its early stages, but a carefully planned campaign of several years since local tourism consultant Terence Stevens had come up with the idea. Perhaps Terry got the idea when he became an officer of ‘Skyline Luge Sheffield Limited in 2018.

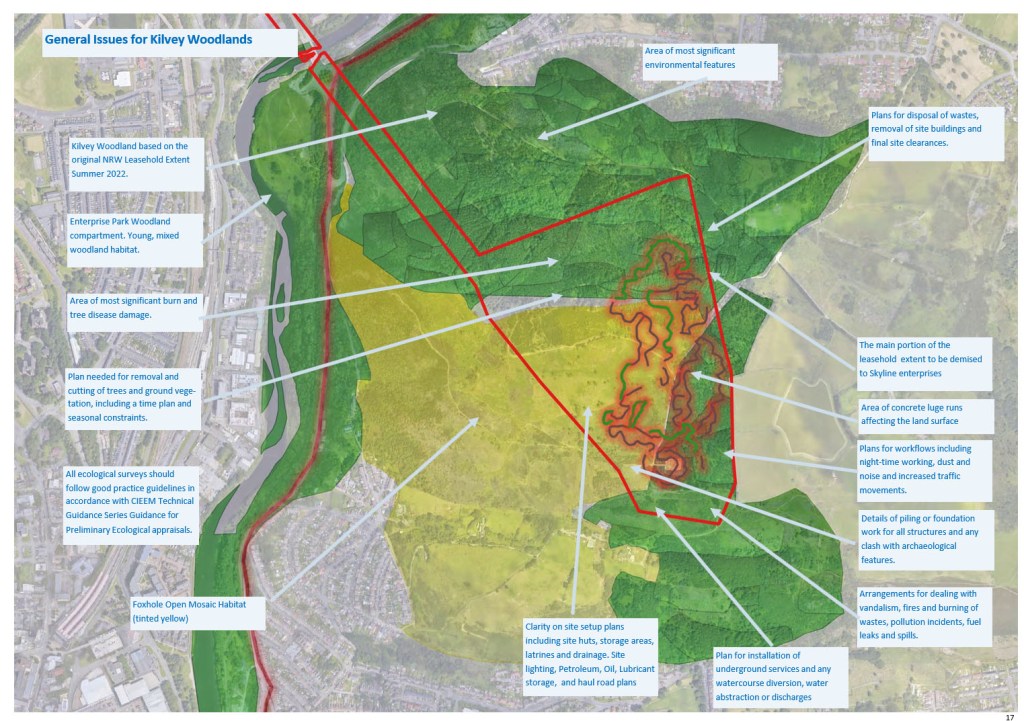

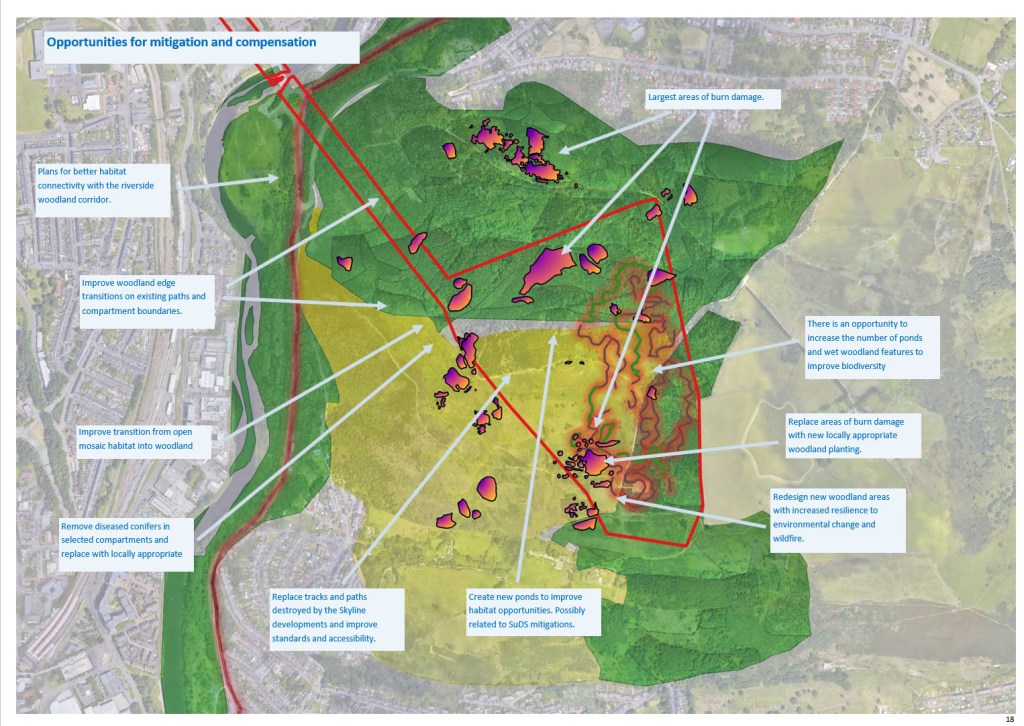

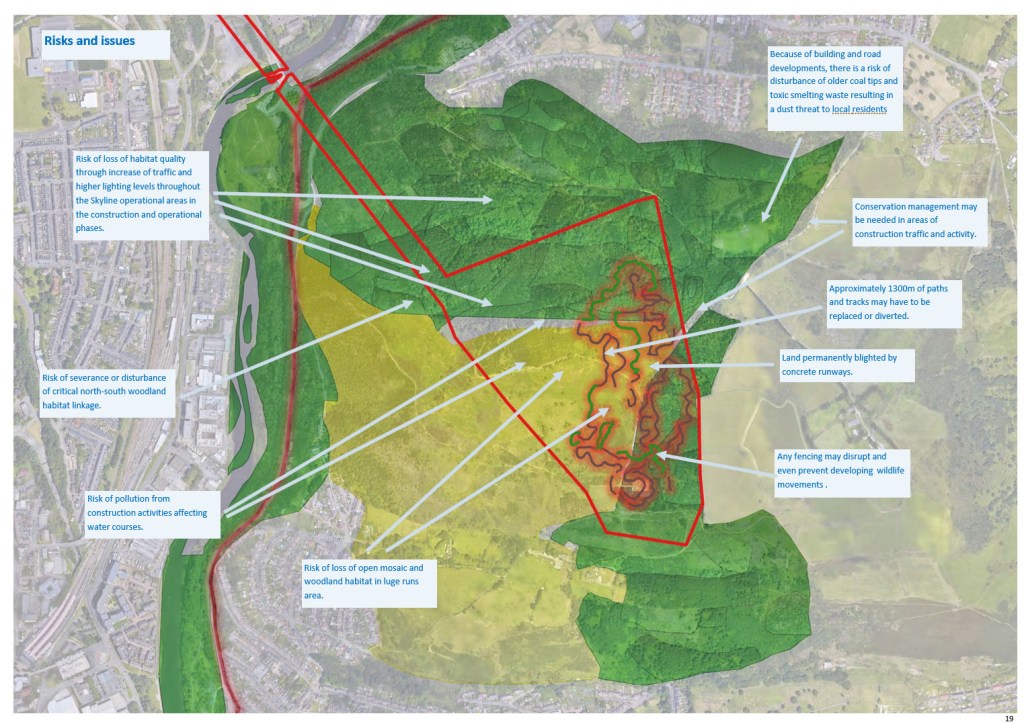

To try to fill the information gap, I created my own Ecological Constraints and Opportunites Plan (ECOP), something I used to do when I worked for the Civil Service. I was trained to follow the common standard BS42020 in structuring a document that brought together the essentials of a building plan that affected the environment.

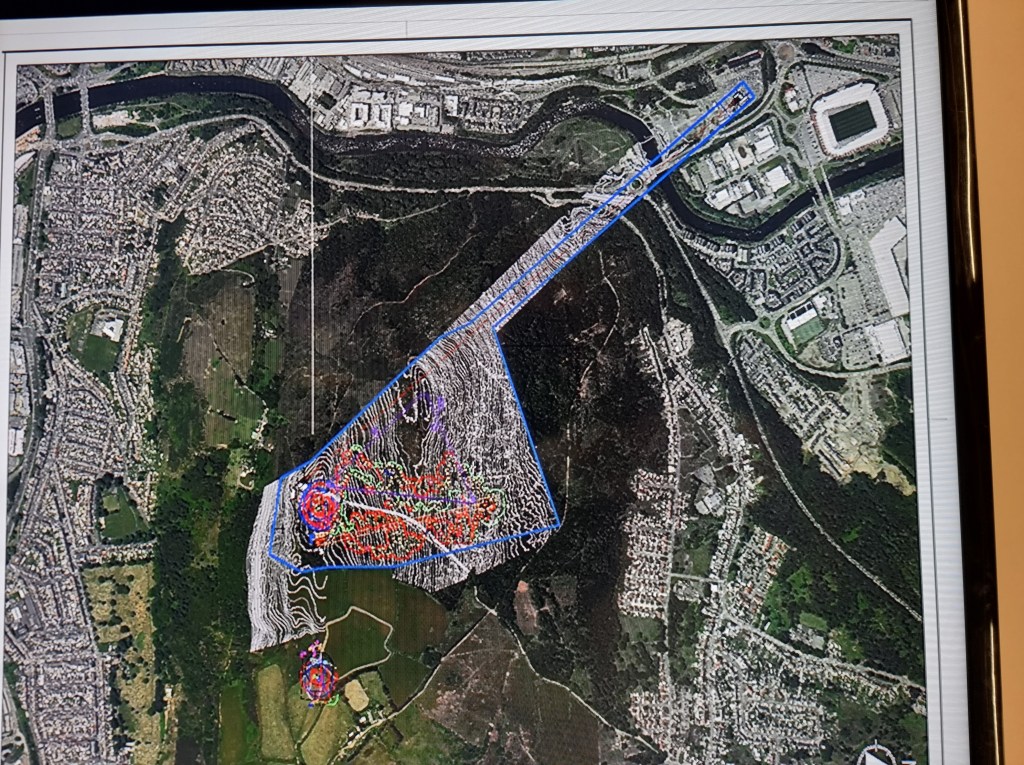

I took a photo of one of the slides on the PowerPoint shown to the meeting on the TV screen they had there. I used that as the basis for investigating the land.

I built up an ECOP over four versions one each month (Jan -April 2023), each building on information I could interpret, but all versions were incomplete. I remember having several aggressive emails from Council staff as I asked for information. I could never work out if they were upset with me for asking or Rob Stewart for giving out vague or misleading information. We’ll never know.

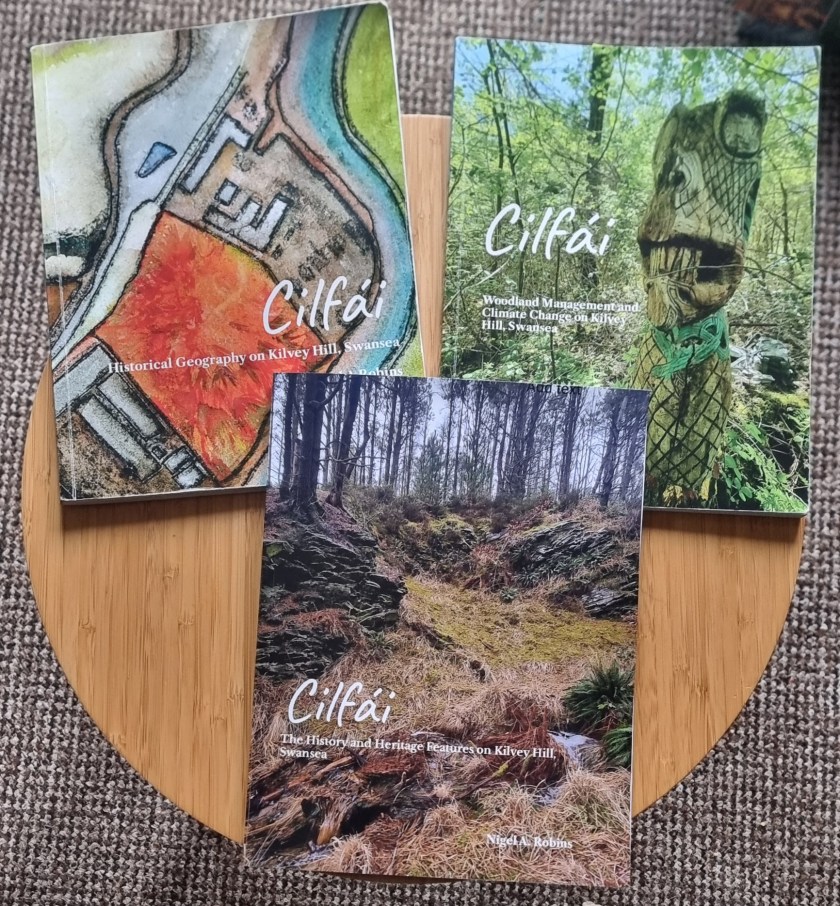

Eventually the ECOP turned into the Cilfái Trilogy of books which have formed a solid basis of information on history, woodland management and heritage for me to teacvh the landscape history of the hill.

As is my habit, I posted the last (fossilised) version of the ECOP on my Academia page. What amazes me is the massive number of downloads of this document (including USA and various African countries) and local authorities. So, I guess my structure is being used as a template elsewhere. Which is great.

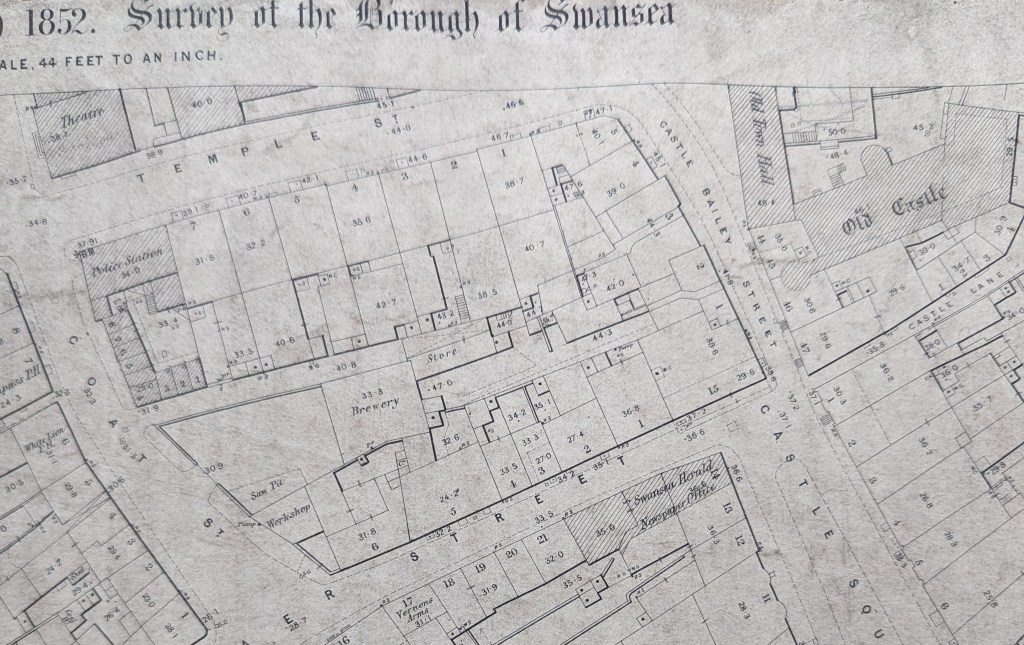

Below are screen shots of one of the versions…