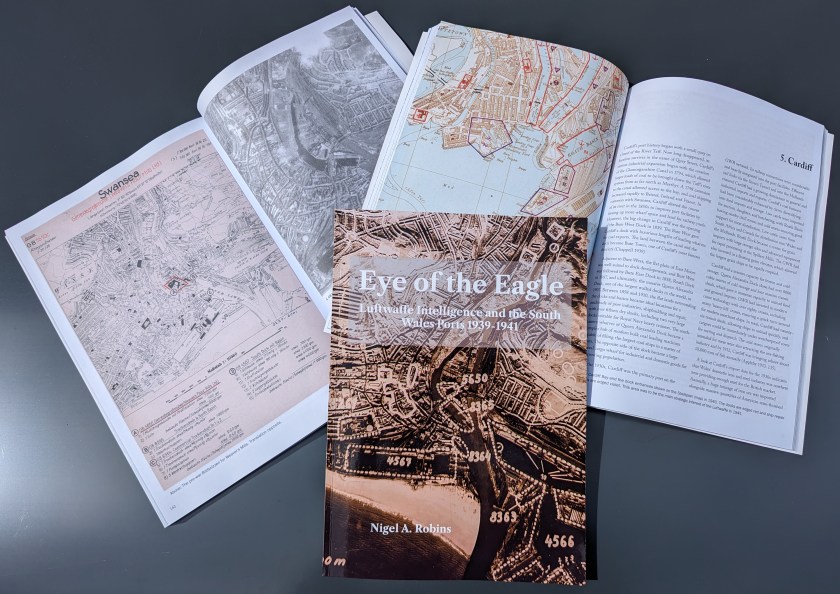

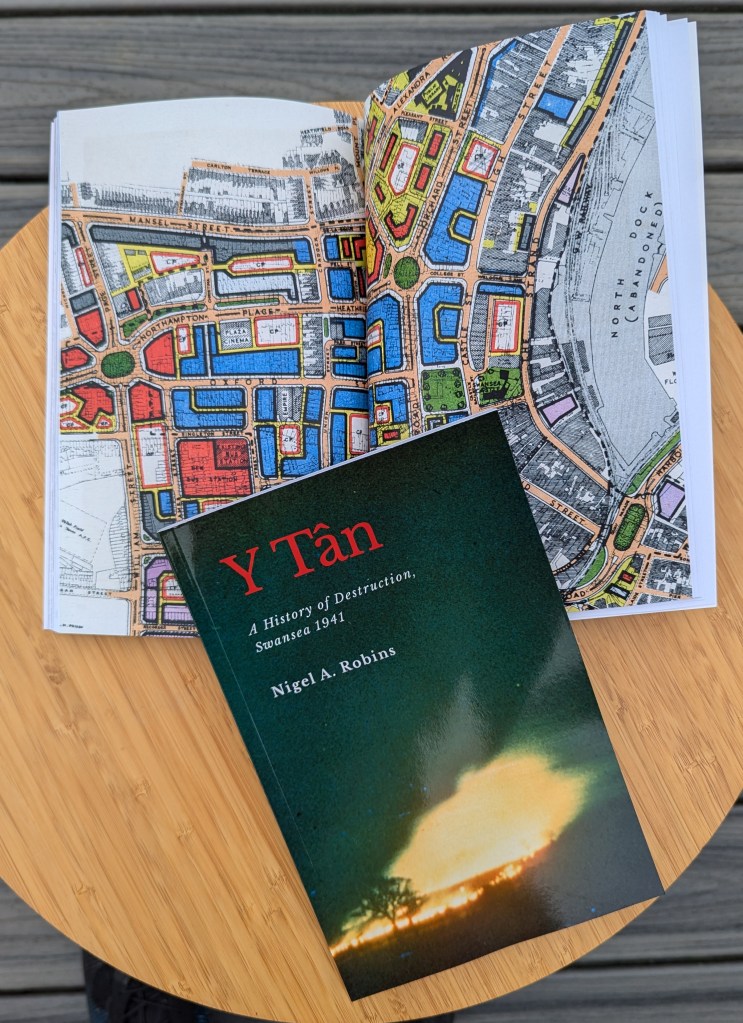

Last Saturday, I discussed publishing my newest book, Eye of the Eagle. The venue was the Discovery Room at Swansea’s Central Library, which has become a focus of contemporary local studies and research for Swansea’s residents.

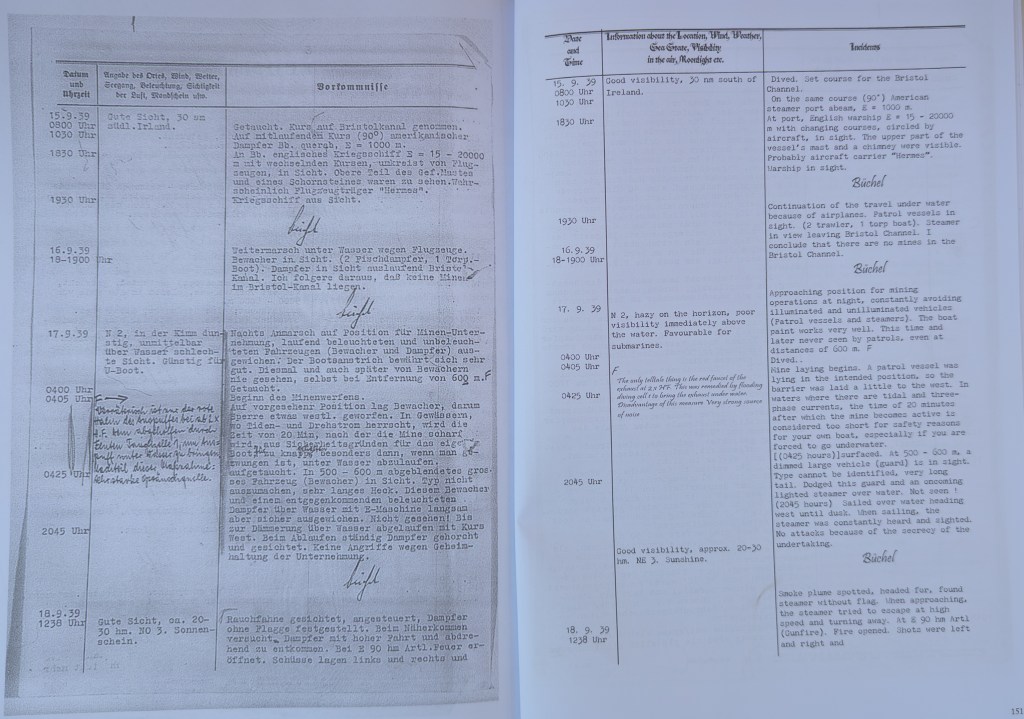

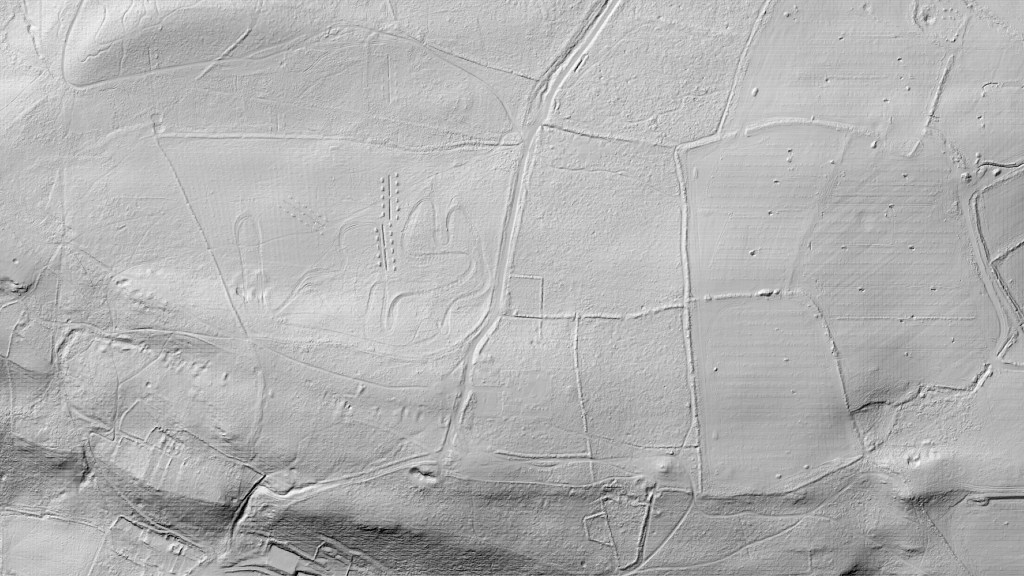

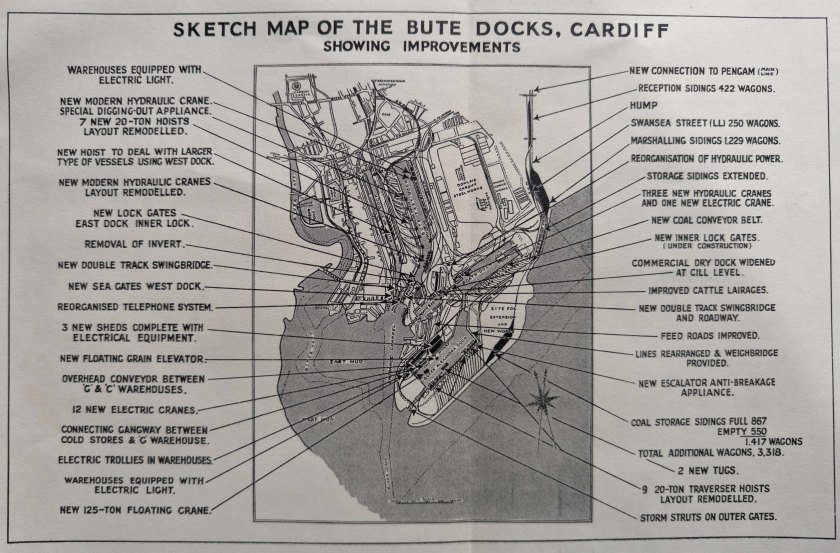

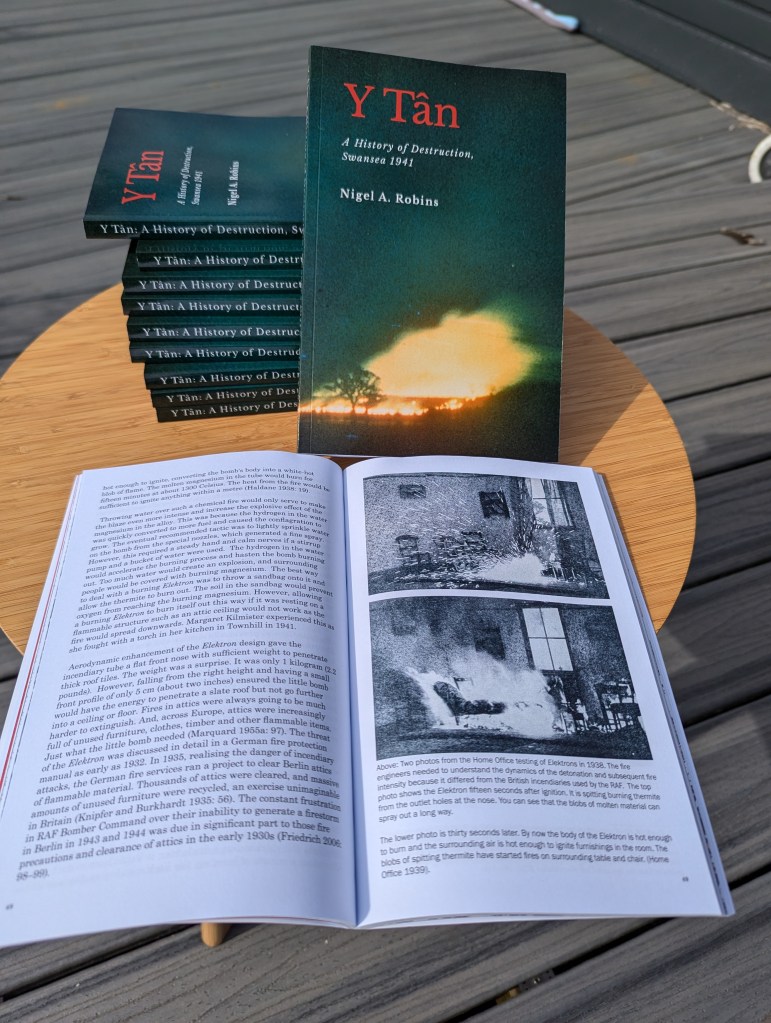

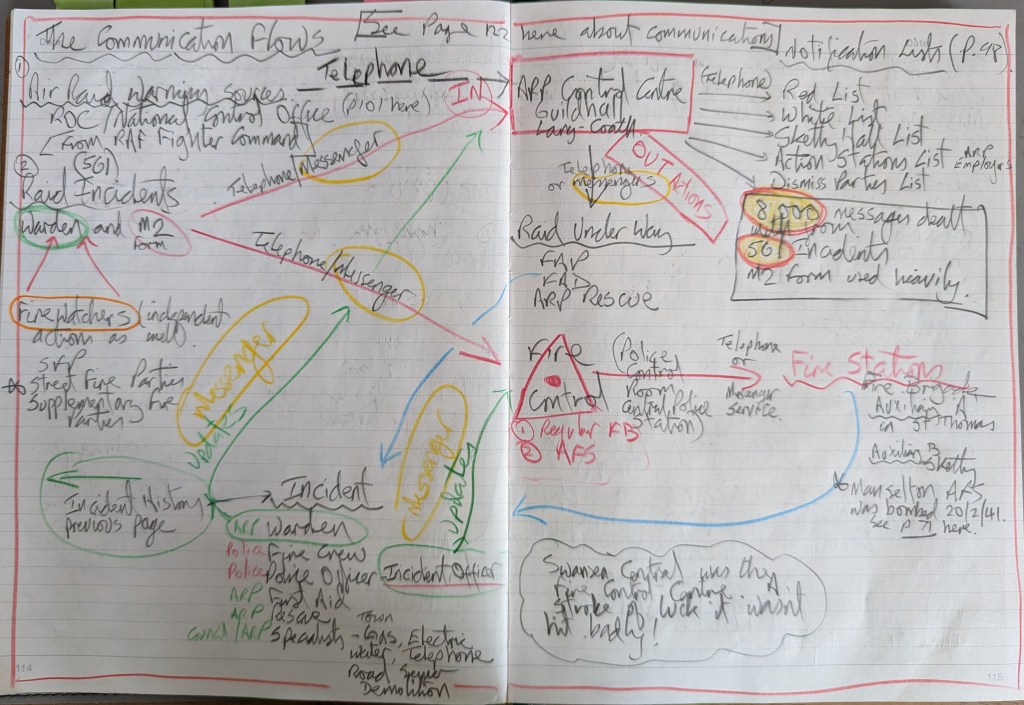

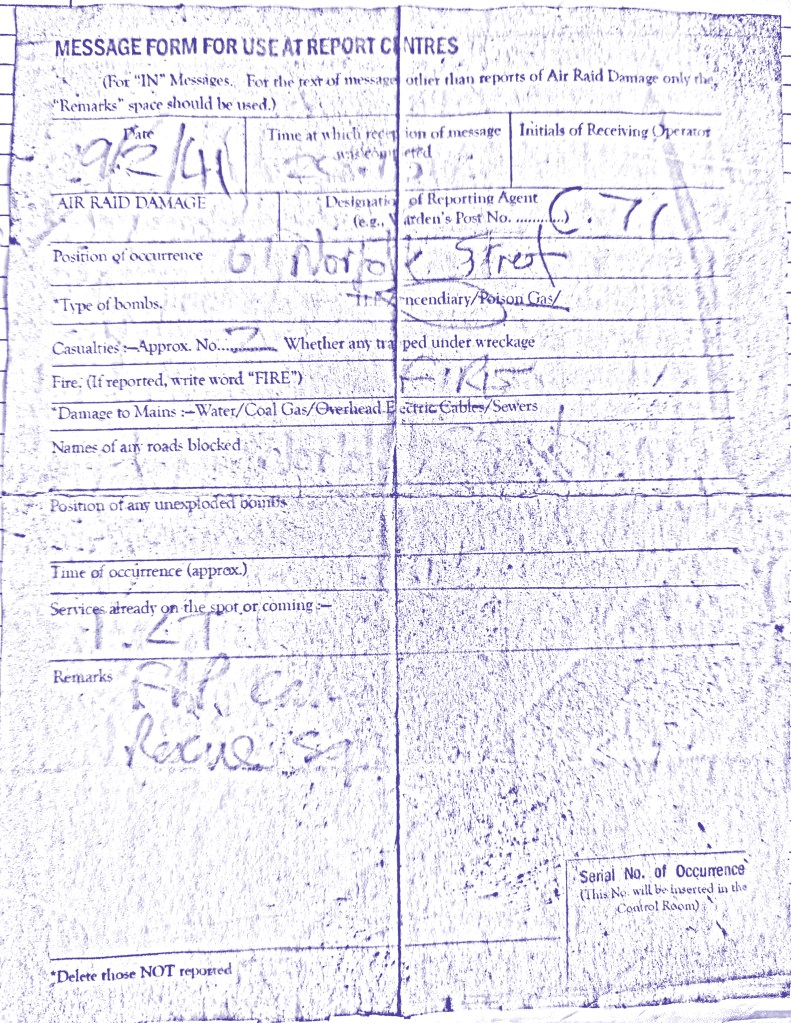

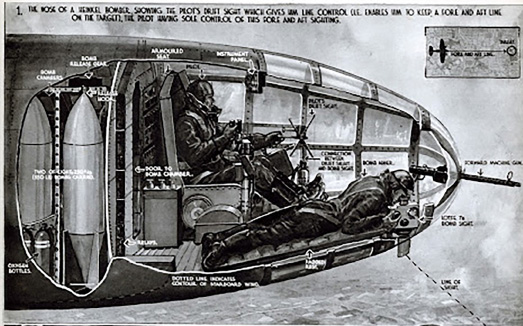

My research on World War Two goes back decades and is primarily concerned with the bombing of Welsh towns and cities and, of course, the maps and images used. All in answer to the questions of how and why.

There is still a massive interest in Swansea’s war years. Many of us lost family members, and many who experienced it are still eager to listen and share their memories. The continuing wars in Ukraine and Gaza ensure images of destruction and suffering are still with us and not confined to history books. In setting the scene for the talk on my research, I mentioned a book that I feel strongly highlights the horrors of modern war and its direct impact on civilians (and particularly children). The book is ‘The Tree of Gernika’, written in 1938 by a journalist witnessing the horrors of the Spanish Civil War as they affected people in Spanish towns and cities. It’s as powerful a book today as it was then (Steer 1938). The author describes the reality of terror bombing and mass slaughter and destruction to a European audience looking on with horror and assuming it was something too horrible to be replicated across the Continent. Of course, we all know that what happened in Spain would be eclipsed hugely by mass attacks on civilians in the following years. The parallels with the Ukraine war are incredible. Despite the media hype about precision weapons, both the Russian and Israeli governments have concluded that terror attacks on vulnerable civilians are more effective and satisfying…particularly when their armies are finding it hard to get a decisive battlefield result . The same happened in 1918 in Germany, Iraq in 1923, Spain in 1936, and South Wales in 1941-43 (Saundby 1961; Alban 1994). You can’t blame Russians or Israelis for today…they took their lessons from the RAF, the United States air forces, and the Luftwaffe.

The title of this post is challenging. Nowadays, Natural History is associated with an Attenborough TV programme. The expression was coined in 1944 by Solly Zuckerman, a renowned war scientist who, upon seeing the blasted remains of buildings and people in Aachen, planned to write an article on the nature of the destruction. On seeing the enormous damage to Cologne in 1945, Zuckerman decided he could never write a sufficiently eloquent piece covering the loss of life in the most awful of circumstances, and he quickly forgot about the idea (Zuckerman 1978: 322).

The phrase was resurrected in the controversial lectures of W G Sebald (One of the finest writers of the post-war years) in his famous book (Sebald 2004). The ethics and issues of mass murder of civilians resurfaced and have never gone away since, particularly after the release of ‘The Fire’, a haunting review of civilian deaths in wartime Germany (Friedrich 2006), and Derek Gregory’s review of Sebald’s work on the true nature of the air war against British and German civilians (Gregory 2011).

I concluded my talk on the bombing of Swansea with this…

“In twenty-five years of research on the bombing of Swansea and the other South Wales ports, I never saw a single piece of evidence that the deaths on the ground (or in the air), and destruction of the towns, resulted in military or strategic benefit for the Nazi government.”

Alban, J.R. 1994. The Three Nights’ Blitz: Select Contemporary Reports Relating to Swansea’s Air Raids of February 1941, Studies in Swansea’s History, 3 (Swansea: City of Swansea)

Friedrich, Jörg. 2006. The Fire: The Bombing of Germany 1940-1945 (New York: Columbia University Press)

Gregory, Derek. 2011. ‘“Doors into Nowhere”: Dead Cities and the Natural History of Destruction’, in Cultural Memories: The Geographical Point of View (New York: Springer), pp. 249–83

Saundby, Robert. 1961. Air Bombardment: The Story of Its Development (London: Chatto & Windus)

Sebald, W.G. 2004. On the Natural History of Destruction (Penguin Books)

Steer, G.L. 1938. The Tree of Gernika: A Field Study of Modern War (London: Hodder and Stoughton)

Zuckerman, Solly. 1978. From Apes to Warlords 1904-46 (London: Hamish Hamilton)