Saving the Environment: The importance of Information

In the early spring of 1941, two people followed in the footsteps of the bomb disposal teams, firefighters and council workers as they worked through the shattered ruins of Swansea’s blitzed town centre. The first was artist Will Evans, who was keen to document the chaos of ruins and the loss of the heart of the town. Evans left a legacy of vivid watercolours that are well-known. However, the other person was naturalist M. H Sykes, who is less well known. Sykes was a member of the Swansea Scientific and Naturalist Society (SSFNS), and she was a competent botanist with a keen eye.

The ’Three Nights’ Blitz’ inflicted grievous damage on Swansea. The air raids and the ensuing fires created over 16 hectares of broken buildings and rubble at the heart of Swansea. It must have been horrendous.

In 1941, across the country, botanists realised that the blitzed landscapes would soon offer a unique opportunity to witness a comparatively rare phenomenon. This was the emergence of ‘spontaneous vegetation’, the pioneer plants that would arise on the broken brick and rubble. The phenomenon was first recorded amongst the ruins of London after the Great Fire in 1666. In 1941, expanses of ruins reappeared in London and blitzed towns such as Swansea along with the newly christened ‘bombsite flora’.

My article on the bombsite floras of Swansea is forthcoming in the next edition of Swansea History Journal published by the Royal Institution of South Wales http://www.risw.org/publications.htm

Coming soon.

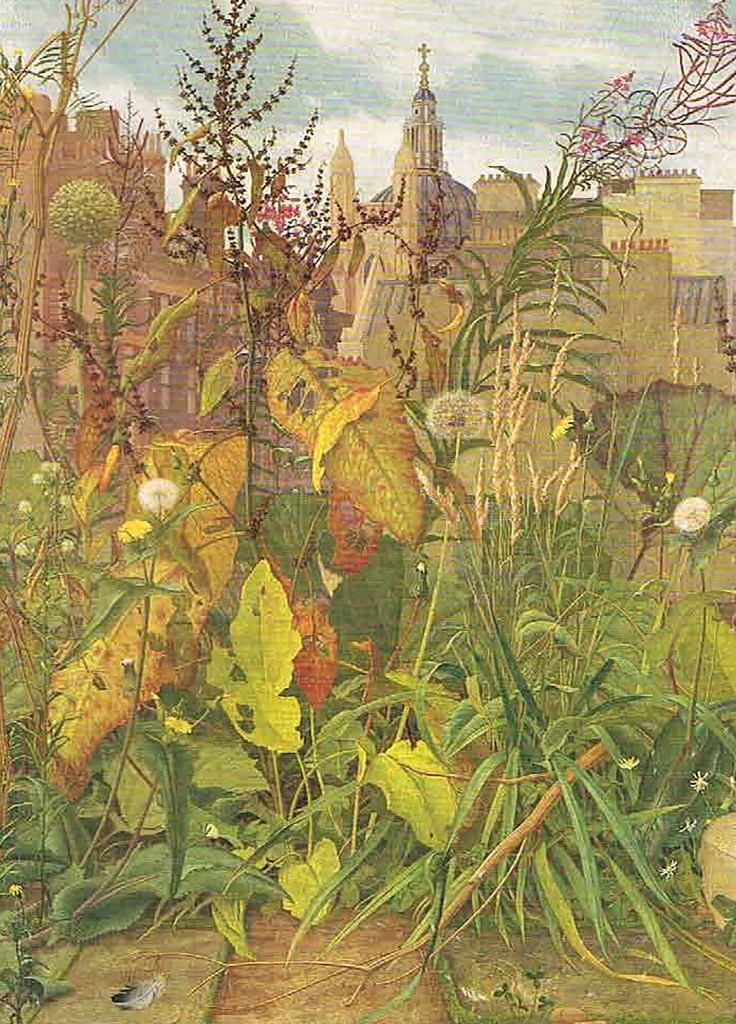

Image: Eliot Hodgkin was one of the very few artists attracted to the contrasts between the brutality of the war ruins and the vegetation that covered them. This is an extract from one of his most notable blitz flora studies of ruins at St Paul’s in London in tempera. Hodgkin was a master of detail and captured the shape and form of many of the blitz plants at their best. The original is in the Imperial War Museum collection.