Who owns history?

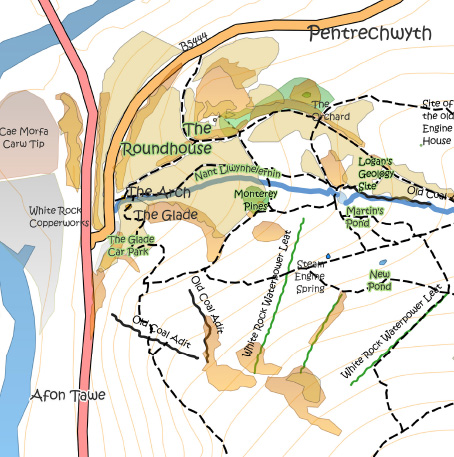

Last Saturday, I talked about the history of Cilfái as part of our National Local History Month celebrations.

I had a packed room in the Central Library, not to see me… but to listen to the topic. Concern over losing our history and heritage is mounting as more threats from local Council plans get closer. I knew many of the audience, some of my old colleagues, heritage and environmental workers, and my past history teachers. There were a lot of local people as well who made an effort to come and sit in a warm teaching room on one of the hottest days of the year.

The combined years of experience in the room were amazing. People who had worked on the hill researched and cared for it, and a newer generation is taking on the challenge of future care. There was an unbroken chain of partnerships and friendships dating back to the pioneer historians Clarence Seyler and George Grant Francis.

The talk and the questions session afterwards led me to reflect on the history I was talking about. Much of the past fifty years of Cilfái history is not documented and runs a significant risk of being ‘reinterpreted’ by an unmindful local authority and a foreign tourism company. That risk of deliberate amnesia was one of the reasons I wrote the Cilfái volumes.

But who ‘owns’ the history? It is always an important question. In 1891, Oscar Wilde penned an often-quoted phrase, ‘The one duty we owe to history is to re-write it.’ Although Wilde was likely thinking more of fine art criticism, the statement holds up in modern times with the revision of colonialism and racism prominently featured in research and popular histories. I’m part of that process as I talk of the environmental pollution and ecocide that accompanied the explosion of industrialisation and exploitation in the Swansea Valley.

As good as the Wilde observation is, I felt I was always led by this statement from George Santayana in 1905…’ Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.’ I suppose the ‘remembering’ or ‘forgetting’ can be both wilful and accidental. In the past month, I have had conversations with senior Council officers over Cilfái, where officials were adamant that records and land titles were entirely in order concerning the hill (and officially stating that was the case) whilst not checking anything about the truth and validity of those statements. The main reason behind their indolence was an intention to wilfully ignore the hill’s history. After my pushback, the senior planning officer had to retract those silly statements. The worst part of the episode was the inherent untruths and misrepresentation of vague facts advanced by Council employees who may be qualified but are rarely experienced. The injured parties are us as the public.

In books and talks about the history of Cilfái, I have tried to open ownership of our history to the broader public to combat the apparent desire of some to shut down debate, consultation, and knowledge. It is also important to remember that some of the most vocal Facebook warriors in unquestioning support for foreign tourism company plans have never been on the hill.